Meet the Deaf architects fighting for more inclusive spaces

A new Deaf-led initiative to design more inclusive buildings and address systemic inequities has launched this summer.

Deaf and hard of hearing people exist on a wide spectrum but our shared experience is one of concentration fatigue. We rely on ‘reading’ visual cues in our environment, not just to communicate, but to stay safe. It creates a constant cognitive load that is invisible to others.

Trying to lipread or follow signing when faces are obscured by light or shadow, straining to hear over echo and background noise and frequently being startled by things we didn’t see coming - it’s wearing. Inclusive and accessible building design can remove these unnecessary barriers.

Every Deaf person will be familiar with the challenges of navigating a built environment that was, unintentionally, created to exclude us. This arises because it was designed without us. Lack of inclusion results in systemic inequity for Deaf people in all areas of life.

"We don’t need ‘building hacks’ for Deaf people; we need fundamental change to develop an architecture that recognises, works for, and enriches everyone.”

Chris Laing, founder of the Deaf Architecture Front (DAF) which launched in June 2023, is determined to change this.

“The change that the DAF and I want to see is not for the architecture sector to introduce add-on tools for the Deaf community to participate in its existing systems, but for those systems to be redeveloped to include all communities. Inclusion, whether it’s for the Deaf community or another group, cannot just be an added extra. We don’t need ‘building hacks’ for Deaf people; we need fundamental change to develop an architecture that recognises, works for, and enriches everyone.”

The only deaf member of his family, Laing was fortunate that those close to him learned how to sign, meaning that British Sign Language (BSL) is his first language. This is an incredible rarity given that 90% or so of deaf children are born to hearing families. Although the attitude is now shifting, sign language has been discouraged for decades, driven by the myth that it will prevent infants from learning English. The result is that access to education for Deaf students remains shamefully poor.

Only when he arrived at the University for the Creative Arts to do his first degree, a BA in interior architecture, did Laing discover that he had rights to access his education in BSL. This knowledge was transformative. Upon completing his BA and inspired by a rare role model - another deaf architect - he then returned to his original ambition to specialise and began his BA in architecture at Kingston University.

The journey to becoming a qualified architect isn’t easy for anyone, but Laing has encountered more barriers than most. The further his studies and work experience progressed, the harder it became to secure the funding needed to provide interpreters, pushing Laing to the point of almost dropping out of his MA at the Royal College of Arts. Yet, as we often find in the struggle towards Deaf and disability equality, it falls on those who are most marginalised to lead the fight for access and inclusion.

As Laing points out, “it’s exhausting. I was told there wasn’t enough funding for an interpreter throughout my MA, and the Disabled Students’ Allowance didn’t cover it all. Following advice from the students’ union I raised a complaint and kept pushing. Then the university found the money. After putting me through all that stress. If this is happening to me, what about others?” At times he felt lonely, not just because of communication barriers but because as a Black, Deaf, gay man he couldn’t see himself represented anywhere.

A turning point for Laing was coming out at university and finding solidarity and a new sense of identity within a wider community. As for his Black identity, “thank you Black Lives Matter. Black faces, I was [finally] seeing Black Deaf people. It brought people together and that was so empowering.”

Identity is core to Laing’s motivation in setting up the DAF. Looking around as a child, he found no role models, which damaged his confidence and left him feeling lost. Although he went to a school for deaf children, it took an oralist approach, discouraging the use of BSL. Most of his friends were white, his teachers were white and the curriculum didn’t include Black history. This provided no opportunity to learn about and embrace his different identities. He doesn’t want anyone else to experience that isolation.

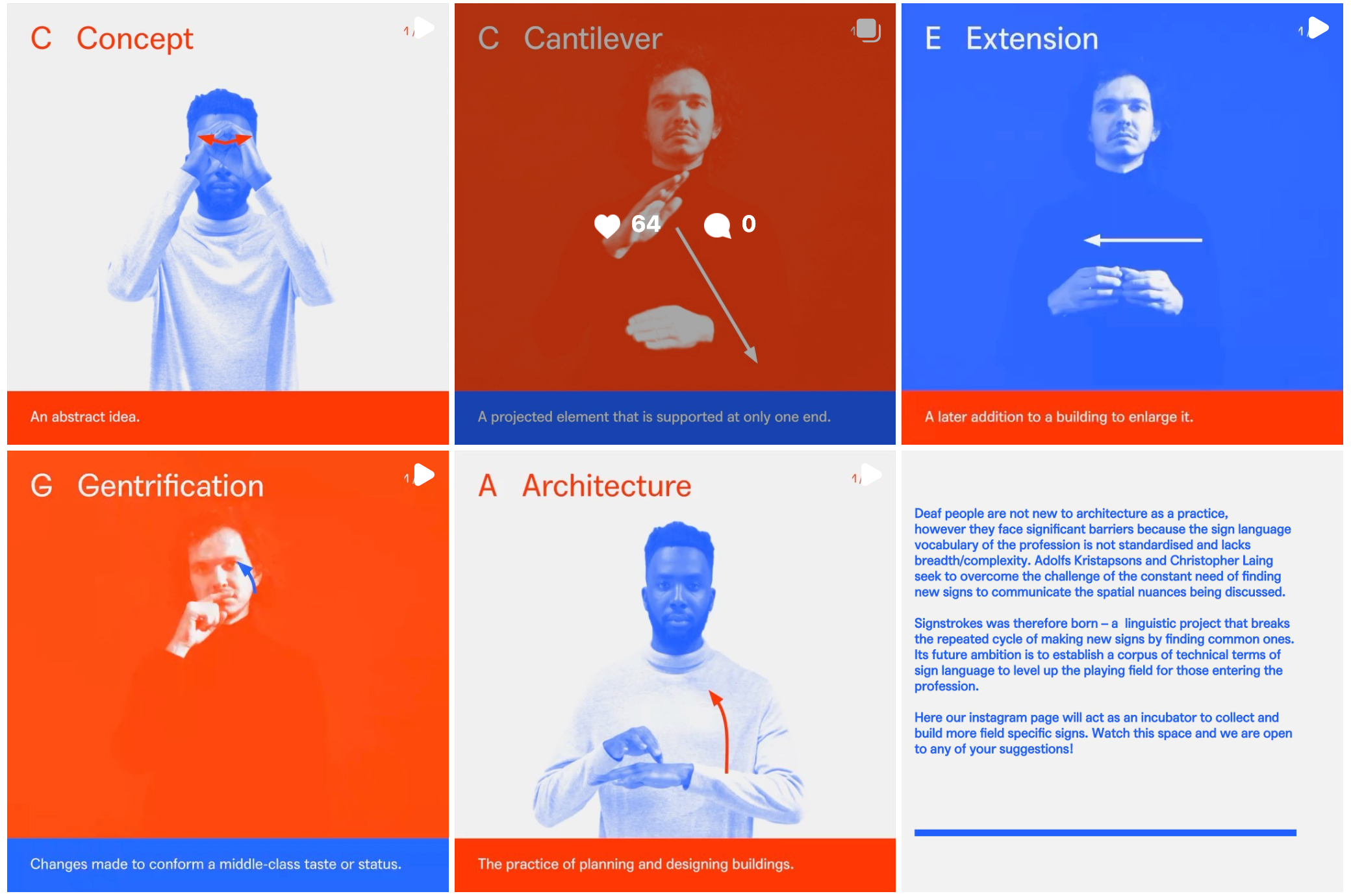

Screenshot of the Sign Strokes Instagram page.

His hope for the DAF is that it will provide a similarly inspiring networking space, connecting Deaf students and architects with opportunities, funding and role models while also being a catalyst for lasting social change.

The DAF’s own research found that “only 3% of qualified architects are disabled, and deaf people make up 0.2% of that” - meaning that there are only five qualified Deaf architects in the UK. 80% of deaf architects who responded said they felt isolated and that they preferred access through BSL over written English.

"We can drive more change in improving accessibility within the built environment and creating stronger communities by working with Deaf architects.”

Additionally, 70% of interpreters lacked familiarity with architectural terms - that created another significant barrier to Laing’s studies. Without a standardised BSL linguistic framework, interpreters resort to fingerspelling long, complex words which are then impossible to absorb. The irony is that BSL is a visual, direct language and perfectly suited to architecture. Ever focused on solutions, Laing worked with architect Adolfs Kristapsons to create a BSL vocabulary, SignStrokes.

Part of the DAF’s work will include expanding the lexicon and training interpreters to use this specialist vocabulary. Alongside this will be visual and BSL resources that explain key architectural concepts. Such an elegant solution opens up opportunities for Deaf people to study architecture but also enables public consultations on design proposals to be made accessible to the wider Deaf community. This amplifies the potential to realise the core aims of the DAF, which seek to create lasting change towards accessible building design – only achievable if Deaf people are included throughout the design process as architects and end users. This is recognised by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

Robbie Turner, Director of Inclusion and Diversity at RIBA, said, “creating a more diverse profession which is representative of communities and societies underpins our work at RIBA. We were delighted to host the recent launch of the Deaf Architecture Front (DAF) and look forward to supporting their work as it progresses. We can drive more change in improving accessibility within the built environment and creating stronger communities by working with Deaf architects.”

Utilising the lived experiences of all the people who use the built environment and considering the needs of Deaf people at every stage of the design and construction process is a vital part of delivering better buildings, creating a sense of belonging and making society more equitable.

Deaf Architecture Front founder Chris Laing. Photographed by Natasha Hirst.

The focus is on radically changing the environment whilst embracing Deaf people as we are. If barriers to our participation can be designed-in, they can also be designed-out.

Enter, DeafSpace. This set of more than 150 architectural design principles was developed over five years at Gallaudet University for Deaf people in Washington DC from 2005.

DeafSpace principles reflect the deeply sensory way in which deaf people interact with the built environment. It encompasses signers who occupy spaces in a different way, needing more space to sign, more open room layouts and clear lines of sight across their environment. Careful use of colour and light reduces eye strain and other design elements can dampen background noise and reverb, benefiting those who use assistive technologies like hearing aids.

These common-sense principles create a far more comfortable experience for people who aren’t deaf too. We can all benefit. The concept of DeafSpace presents an important challenge to audism (discrimination against Deaf and hard of hearing people) because the focus is on radically changing the environment whilst embracing Deaf people as we are. If barriers to our participation can be designed-in, they can also be designed-out.

Yet it is still rare to find inclusive features in the built environment.

Laing explained, “when I was researching for my MA on inclusive design for deaf people almost nothing existed. Why is this the case when DeafSpace has been around for 13 years? The DAF is campaigning for adjustments to existing accessibility guidelines to incorporate these principles.”

There are huge ambitions for the DAF but it is a considerable amount of work that requires resources. Laing aims to set up a structure that allows the DAF to secure funding and develop further partnerships.

As well as campaigning for change and building the SignStrokes vocabulary, the DAF will develop practical resources, such as how to book interpreters, and apply for funding such as the Disabled Students’ Allowance or Access to Work.

The systemic inequalities that Laing is challenging within the built environment are replicated everywhere for Deaf and disabled people. The Deaf Architecture Front has far-reaching potential, demonstrating what inclusion looks like in practice and relieving future generations of Deaf students from the uphill battle Laing has experienced.

Laing himself is now faced with the next challenge, to make it possible to take his lengthy level 3 exam in BSL instead of written English. Then, he will be a fully qualified architect, a dream he’s held since he was eight years old.

Asked what he hopes the built environment will look like in twenty years’ time, Laing is quick to answer. “DeafSpace, everywhere. That’s what I want to see.”

A quick note on terminology:

- This feature embeds the social model of disability, developed by the UK disability movement. It refers to the way that barriers in society disable people with impairments or health conditions. The social model aims to remove these barriers instead of expecting disabled people to adapt themselves to fit into a disabling world.

- In line with the social model we use the term disabled people (not people with disabilities, although this term is often used in the US).

- There is a distinction between Deaf and deaf - Deaf refers to members of the Deaf community and (usually) first language BSL users - deaf refers to the wider spectrum of people with hearing loss, who may or may not use BSL.

- Please don't use the terms 'The Deaf' or 'the disabled', which results in 'othering' people who are already marginalised. Use Deaf/disabled people or the Deaf community.

- Some Deaf people subscribe to the cultural model of Deafness, viewing themselves as a linguistic minority and do not consider themselves to be disabled.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.