A Very Different Biennale

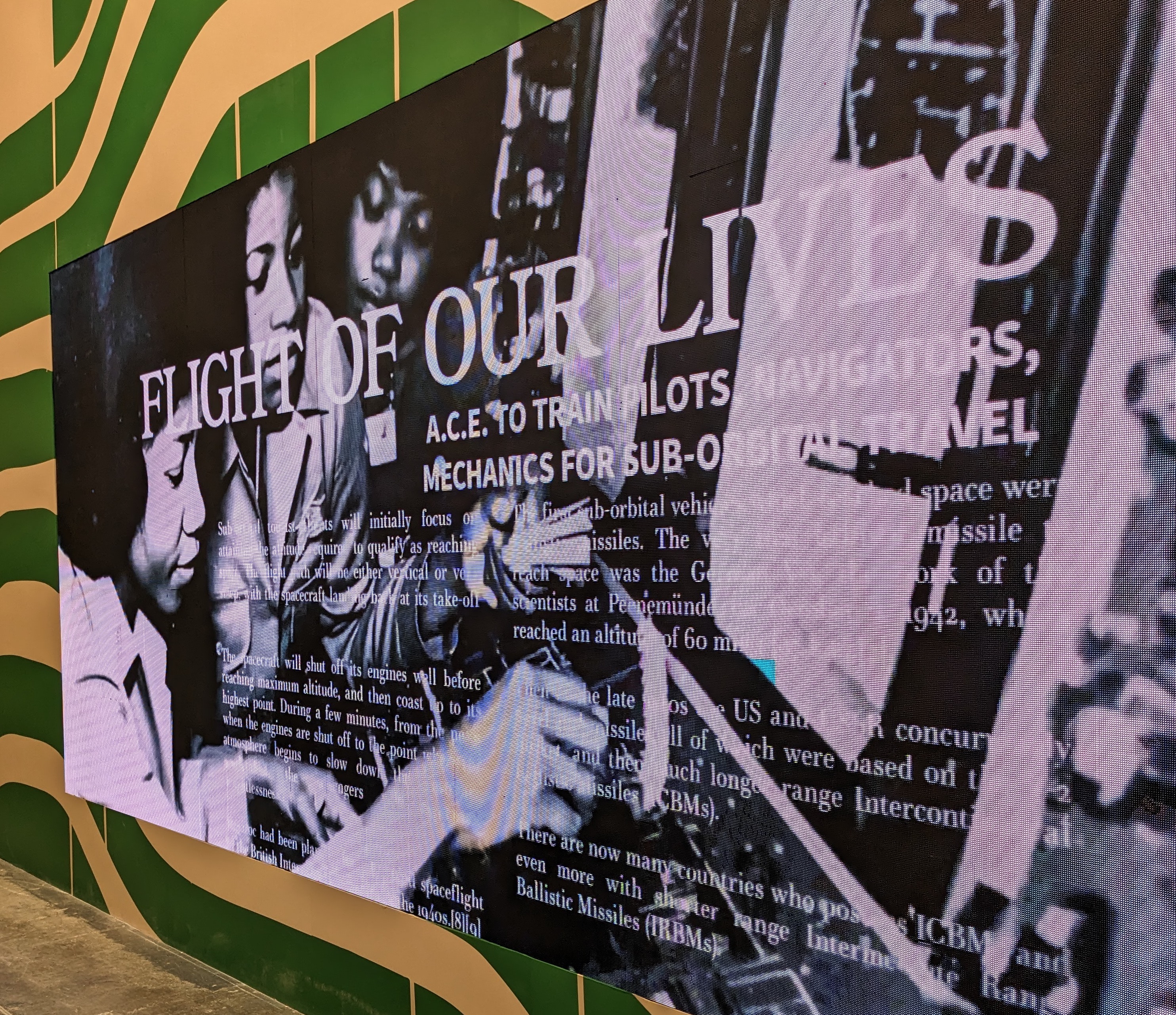

The 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by Leslie Lokko, feels like a radical subversion of everything you might expect from the world's main architectural exhibition - deposited right into the heart of the artistic establishment.

When we were first planning to attend the Venice Architecture Biennale to prepare a series about the exhibition and the concepts dreamed up by the practitioners (watch this space!), I didn’t know what to expect. True, the Biennale was curated by Ghanean-Scottish architect and novelist Leslie Lokko, and centred on “Decarbonisation and decolonisation”; true, it emphasised learning from architects and artists in the Global South. But I had my suspicions.

My limited experience of world-renowned artistic spaces always left an impression of elitism and exclusivity, cliquiness and superiority. I fretted that I would stand out because none of the clothes I packed were designer, or because these spaces are historically overwhelmingly white.

The Biennale was nothing like this. This was not the self-congratulatory playground for privileged artists. It felt like a radical subversion of all of those expectations - deposited directly into the heart of the artistic establishment. As the first ever curator of African descent, Lokko’s specific vision seems to be behind this fundamental shift in the culture of the event.

I felt fired-up from the moment I arrived - which came as a complete surprise, not because I am uninterested in art or architecture, but because I never expected to feel so welcome.

For the first time, the majority of the exhibitors are from Africa or the diaspora. The exhibition boasts a 50-50 gender balance, and an average age of 43 - which is young by architectural standards. It’s a drastic and necessary redressing of the balance after almost two decades of a dominant Euro-centric output. The show is firmly forward-thinking, with Lokko making a statement about who will (and should) lead the discipline of architecture into the future.

The decolonisation and decarbonisation themes flow seamlessly together - not just as an instruction for the future, but as a new way of looking at the present and the past

This deep sense of inclusion bleeds into every element of the show. I could feel it in the British Pavilion as I watched a film that featured families that look like mine, celebrating the rituals, the food, and the music specific to British Caribbeans and British Asians. I felt a joyful swell of recognition at the archive footage of Notting Hill Carnival, and the gentlemen of the Windrush generation playing Dominoes with a ferocity that triggered a deep nostalgia in me.

I could feel it in the futuristic 'All-African Protoport’ - a space imagining a continent without the hangover of colonialism, a transport hub based on green technologies and Indigenous knowledge, designed by Nigerian-born Olalekan Jeyifous. Set up to feel like a departure lounge, the space lulled me to one of its deep wooden benches and I sat for a while relishing in that transient timelessness specific to airports, overlapping with a timelessness - or out-of-timeness - of another sort.

This isn’t to say the exhibition has entirely broken free from its elitist, white-washed past. I wouldn’t want to imply that a ticketed art show being held in Venice - one of the most expensive cities in Europe - is now fully accessible to a wide range of social and cultural demographics simply because there is greater African representation among the artists. And there are still questions to be asked about waste, sustainability and the environmental cost of putting on a show of this scale. But it does feel as though it is, at least, making positive changes in the right direction.

Lokko’s easy warmth and relative accessibility have set the tone for an altogether different event this year. Underpinning everything she has achieved with this sprawling, ambitious exhibition, there is the clear desire to bring people in. The result is an artistic and cultural event that feels actively, urgently inviting rather than passively or formally inclusive, which Lokko has rightly identified as a vital element in exacting change. And the decolonisation and decarbonisation themes flow seamlessly together - not just as an instruction for the future, but as a new way of looking at the present and the past.

“The Black body, or the ‘other’ body, was Europe’s first unit of energy,” Lokko tells us. “In order to colonise something, you have to think of it as not human or not like you. This allows you to carry out all kinds of exploitative practices.

“This extends to the natural world as well. When we think of nature as ‘not like us’, then we have no responsibility to care for it.”

As I wandered through the maze of groundbreaking, innovative work - from waterless compostable toilets, to detailed plans to repatriate artefacts stolen from the African continent - I was struck by the curator’s knack for making this work entirely understandable without compromising on complexity or nuance. When the topic in question is a matter of life or death, the survival or demise of the planet, there is no place for exclusionary politics or in-group obscurity, whether intentional or not. Clarity and open doors are the Biennale’s best shot at making this work matter beyond their insular spheres.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.