Hunt's Budget: You've never had it so bad

A latex glove in one hand, a polishing cloth in another, the Chancellor tried putting a sheen on our worst downturn in centuries. It didn't take.

You can’t polish a turd, but this hasn’t stopped Chancellor Jeremy Hunt giving it his best shot at this year’s Budget.

It’s hard not to admire the cheeky optimism of a man prepared to offer new forecasts of the biggest decline in living standards in perhaps 200 years as a sign of improvement, simply because previous forecasts had promised us an even more disastrous slide. The British economy, Hunt declared, is set to avoid a “technical” recession this year, meaning only that it will not shrink for two successive quarters – not that it won’t, in fact, shrink overall. Forecasters at the Office for Budget Responsibility are suggesting a small decline over the year, and no one is likely to notice one way or another, with real incomes predicted to fall this year and next. By 2028, the OBR thinks we will still be poorer, on average, than before the pandemic, which suggests real wages will not have recovered to their 2008 levels - two decades after the global financial crisis erupted.

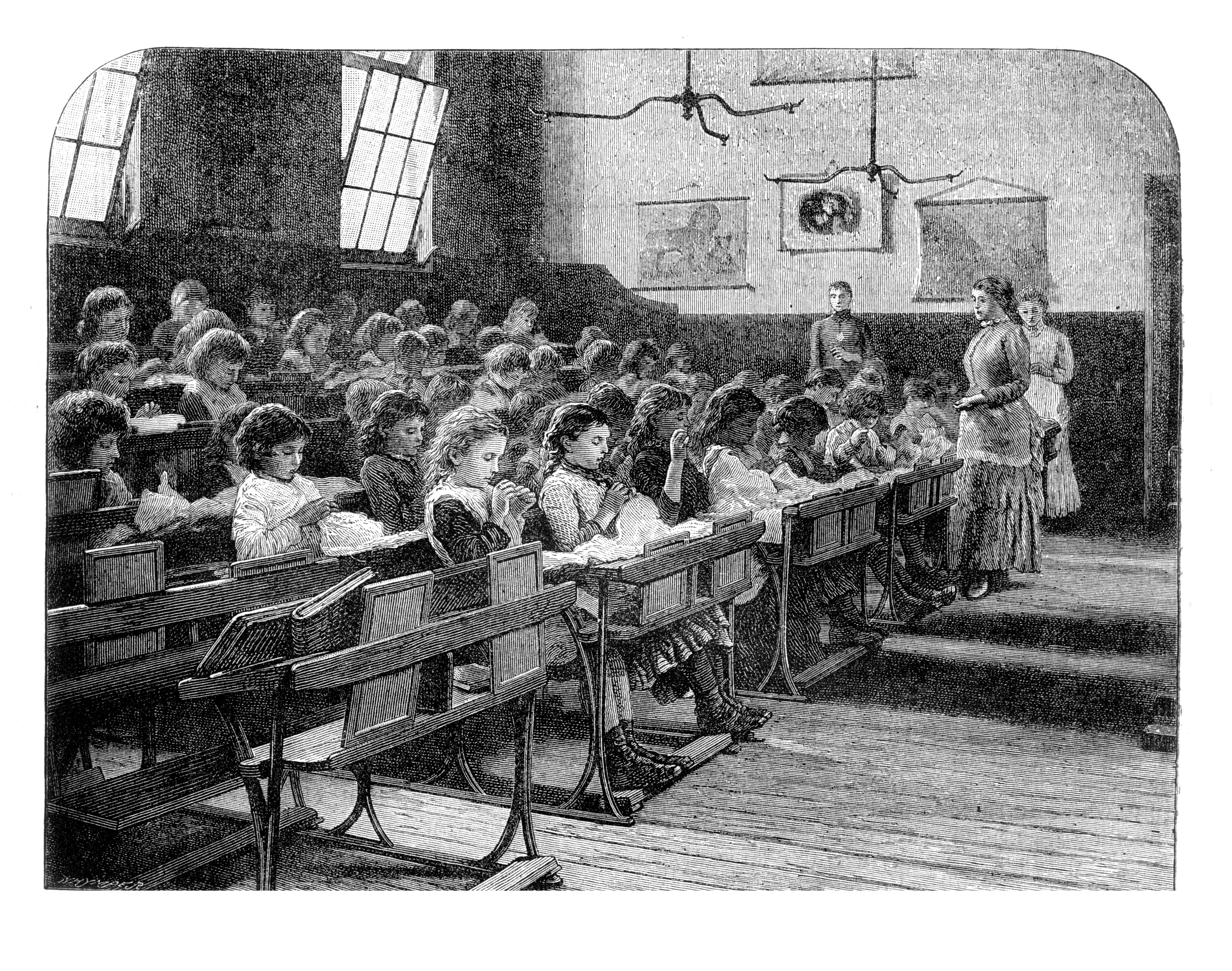

There has been nothing like this stagnation in modern British economic history: the 1970s still get used as a reference point, but average real wages were higher (much higher!) at the end of the 1970s than the start. Even the 1930s saw real wages in Britain higher at the end of the decade than the start. The closest comparison to what we are going through today is perhaps the early years of the Industrial Revolution, when mass impoverishment was the mighty stick driving hundreds of thousands into the industrial towns and cities. Living standards for most worsened until around the mid-19th century, and have consistently improved for most of us, bar the odd recession, ever since – until the 2010s.

It's worth setting out this longer term story because it is the real context behind the Budget. British politics isn’t particularly well-adapted to dealing with the big picture, long-term problems. And while it is certainly possible to say that a general malaise has overtaken capitalism in the last decade or so, with global growth, post-2008, weaker than before and now the impacts of climate change making themselves felt, the British economy has by and large performed significantly worse than other, comparable countries.

Turning this grim situation around would require, as a minimum, a commitment to never again return to the austerity spending cuts of the 2010s

It is on living standards that the failure has been most apparent. While some overall economic growth has happened in the last decade, wages and salaries, after allowing for inflation, have typically fallen. Austerity didn’t just remove a staggering £500bn from public spending over a decade; evidence presented by the Progressive Economy Forum suggested it directly contributed to our low-wage economy. Once the government started trying to squeeze the pay of its own workers, from teachers to nurses to civil servants, it helped undermine the pay and conditions of workers across the economy. In combination with further restrictions on trade union rights and efforts to weaken rights at work more generally, the result was to encourage the creation of a large number of lower-paid, often insecure jobs in the private sector. For all the attempts by Hunt and other leading Conservatives to point to the global economic picture and the headwinds the economy faces, it was decisions by Conservative-lead governments from 2010 onwards that have left us significantly worse off today than we might have been.

Turning this grim situation around would require, as a minimum, a commitment to never again return to the austerity spending cuts of the 2010s. Boris Johnson at least grasped this much, loudly declaring his opposition to austerity and, even before COVID struck, increasing public spending overall. His eventual successors, after a brief Liz Truss interlude, seemingly do not grasp even this: Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement last November pencilled in a return to spending cuts by 2025, allegedly to deal with rising debts and deficits – although he and Rishi Sunak have had the political good sense to try to park cuts until after the next election.

Yesterday’s Budget offered no respite here; in the teeth of high inflation, and with hundreds of thousands of protesting public sector workers outside, this Budget implies real terms cuts to at least some government spending over the next few years because it has allocated insufficient new funds to match higher costs.

Of course, Hunt made a great show of the official forecasts showing a rapid decline in the rate of inflation over this year, down to 2.9% in December. Forecasts can, of course, be wrong, and economic forecasts typically are. The OBR has been notoriously optimistic since 2010, regularly predicting the imminent arrival of broad, sunlit uplands that somehow never quite materialise. The Bank of England, which also attempts its version of economic soothsaying, thinks inflation will still be around 4% by the end of the year. Both could well turn out to be optimistic. And although it is likely the government and its supporters will be slippery on this point, “falling inflation” does not mean prices are actually coming down. It simply means they will not be rising as fast. The OBR and the Bank of England are saying that you will be made poorer more slowly this year, not that you will be made richer – exactly the opposite. They think you will be significantly poorer.

There is little sign the current government has any inclination to address either the root causes of Britain’s strikingly weak economy, or even the more immediate problems of falling public sector pay

Hunt offered not a peep on the question of pay. Support for household energy bills will be extended by three months, and free childcare will be offered to parents of 1 and 2 year olds, both of which will help with rising prices – although with energy bills still set to sit at £2,500 a year for a typical household, and free childcare not available until 2025, it’s not likely many of us will notice.

His major measure to deal with the crisis of recruitment and retention in the NHS, with over 130,000 vacancies waiting to be filled, was an extraordinarily generous £4bn bung to the wealthiest employees approaching retirement, who can now fill their pension pots with significantly lower taxes. This was allegedly to encourage more senior doctors to keep on working and refuse the lure of early retirement, but will be of far more benefit to those far richer than a typical senior consultant; and, in any case, will do nothing to address the crisis in recruitment for nurses or junior doctors. To fix this, and mounting difficulties across the public sector, Hunt will need to pay people more – the money is there to do it, with a 10% pay rise across the public sector costing around £18bn, easily inside the improvement to the public finances the OBR reported since autumn.

The stagnation will continue. To the succession of geopolitical upsets and ecological tremors, we can now throw in the increased risk of a financial crisis, as Credit Suisse applies for emergency government support. There is little sign the current government has any inclination to address either the root causes of Britain’s strikingly weak economy, or even the more immediate problems of falling public sector pay. Their political strategy has become clear in the last few weeks: resolve the most immediate difficulties in Brexit, try to stabilise the economy, and focus attention instead on “culture wars” and migration, of which the furore around small boats is the latest example.

It is brutal, but it can be made to work for them – and while Labour have grabbed with both hands at the free political gift of the pensions tax cut, the party does not yet have a clear counter-offer to the emerging Tory pitch. Whatever polls now say, and however bad things may become, if it can’t present a clear, widely-understood alternative, next year’s election will not be the 1997-style triumph some in the party are kidding themselves with. And this is, perhaps, the real secret behind Hunt’s relentless cheeriness.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.