How the arts can save democracy

Workshops mixing politics and play, community and craft, are revitalising democratic participation in a more direct way than a distant parliament ever could.

Right now, inside a multi-coloured dome on the grounds of a community library in Rotherham, a group of strangers are sharing their fears, hopes, and visions for the future. They are probably also sharing a meal. They might also be fiddling with clay, or mending their old jeans. Some kids on bikes are hovering by the edge, wondering whether to disrupt or get involved. A shed, transformed into a radio station, plays a selection of interviews by another group of people, from somewhere else. In one moment the conversation in this dome is earnest, almost sombre, and the next there is a ripple of laughter. They are sat in The People’s Palace of Possibility and this is what democracy looks like.

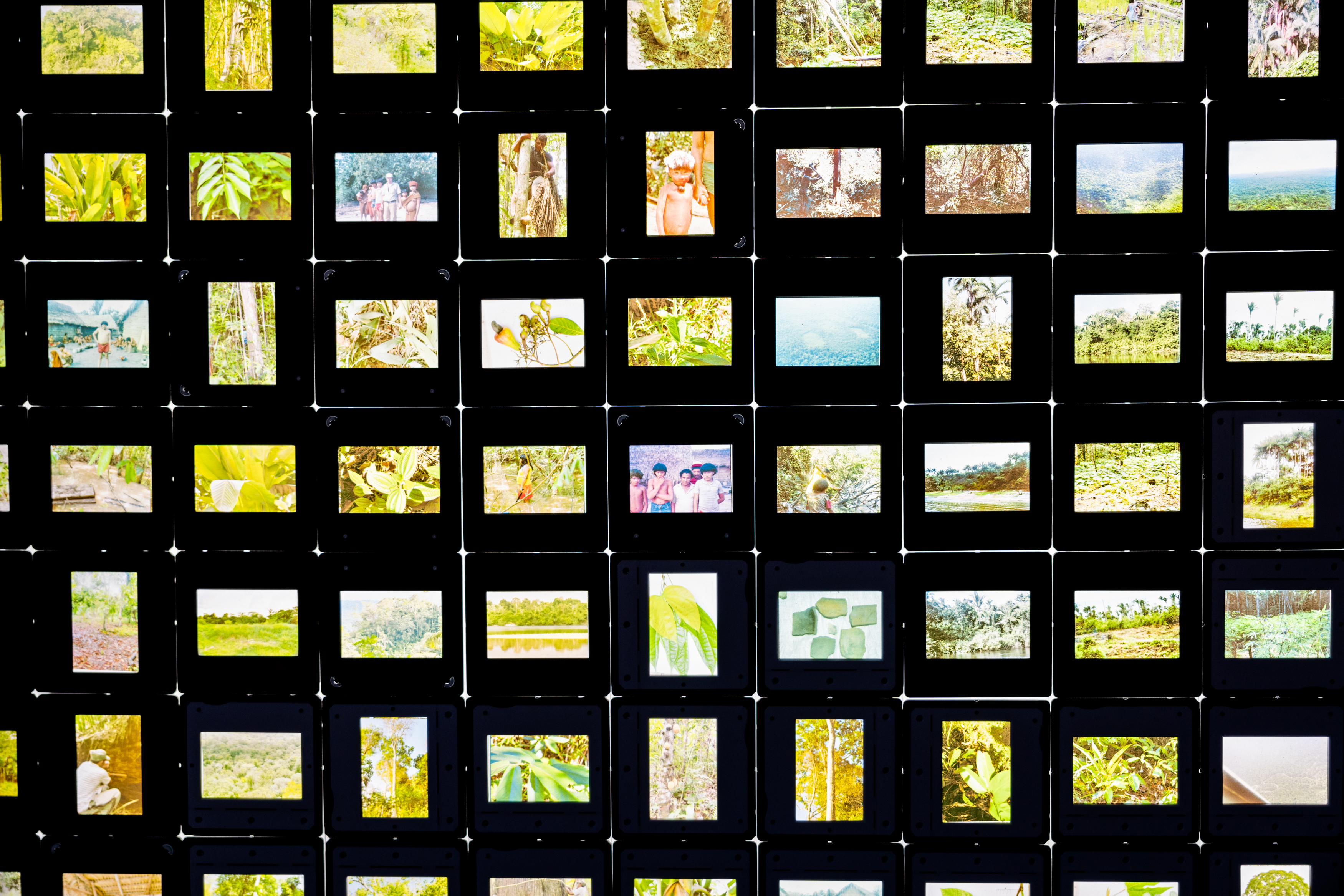

Born out of a postal arts project during the Covid-19 pandemic, The People’s Palace of Possibility now exists as an outdoor installation by Sheffield-based theatre and interactive arts company The Bare Project. Last month the Palace was in the Scottish Highlands, before that it was in east London, and in 2024 it will make the journey to the Isle of Wight and beyond. It is added to and animated by local people wherever it goes. In the Highlands there were ceilidhs, a disobedient choir and drawing workshops; in London there was weaving, clay modelling and audio artworks. Rotherham will host craftivism, street parties and stories of resistance. Every location adds new things to the Palace but it is all brought together by a common question: how do we find energy for the future, despite the fear and anger we feel today?

This work is inspired by the late sociologist Erik Olin Wright and his work on ‘real utopias’. He argued that optimism is necessary for the world to be transformed – we must believe other worlds are possible in order to change it. We cannot face the oppressive forces of capitalism with only an agenda of destruction; we also need desirable, viable, and achievable alternative visions for society.

The term ‘real utopias’ is a contradiction in terms. Utopia literally translates as ‘no place’ – they are an imaginative exercise. Wright acknowledges this and embraces “this tension between dreams and practice”. He argues that rather than using utopias as the wholesale re-imagining of society at large, we can seek out and learn from smaller, more specific utopian endeavours which are already out there in the world. These projects represent fissures within consumer capitalism and by understanding, expanding, and supporting them, we can widen these cracks to collectively oppose and re-build harmful social structures.

Our current democratic system is failing us. It has been hollowed out over forty years of privatisation, underfunding of local government and public services, and a monopolised and commercialised media. More than these specific policies, there is a pervasive, internalised ‘neoliberal rationality’, in which we see ourselves primarily as consumers rather than citizens. Through this lens even our votes are there to be ‘spent’ on whichever party best appeals.

“All our utopian scheming will be flaccid if they do not acknowledge what’s going on for us right now.”

But democracy was never meant to be one vote spent every few years. Its promise of self-governance requires active participation, disagreement and compromise, and collective visioning. And this is essential for a functioning society, particularly when we’re trying to move towards a world that is more environmentally just (which must be underpinned by social equity). Sustainability requires society to constantly adapt. A healthy democracy which is reflexive, imaginative, and deliberative is essential to the process of sustainability, as well as social justice. It is not only about formal elections and policy making, but a ‘culture of democracy’ in which there are multiple and diverse opportunities to discuss our ideas, hear different perspectives, and explore alternative visions for the future.

Everywhere the Palace goes, it seeks to create these opportunities and respond to local issues and contexts. In London rest and productivity came up again and again. An activist shared their experience of burnout and how they approach their work differently now. A local woman, in training to be a pastor, sang gospel songs on the Palace Radio, underlining her faith as her source of hope for the future. In the Highlands conversations often revolved around land ownership. We met Matilde, a young land owner, who, through conversations in the Palace, began thinking beyond the rewilding and environmental conservation of their bogland, towards notions of community and collective ownership as a part of sustainability. We screened a controversial film about nuclear power as a cornerstone to green transitions (particularly relevant to the community given the central presence of Dounraey nuclear site in the area) and ended up staying an hour afterwards with local residents of all ages weighing up the pros and cons. The issues are hyper-local, personal even, but through the Palace they are entwined with the broader issues spanning the length of the UK.

The Brazilian theatre-maker Augusto Boal once described his work as ‘a rehearsal for the revolution’, and the Palace has been created with this phrase in mind. Voicing your anger about a new coal mine on the Palace Radio or modelling an alternative housing system out of clay isn’t going to immediately change policy. But these gestures and rehearsals still have meaning: they clarify our thinking, and they tell us that our opinions matter.

Most importantly, this work connects us with others who are angry, and who have ideas for what could change - locally as well as nationally. The decision to tour this work emerged from responses in the postal version in which people voiced their feelings of hope and energy on a local level, but said they felt a lot of fear when they thought about the world beyond their community. After all, democratic fatigue is entwined with a sense of isolation and futility: does anyone but me care? This work seeks to put you alongside others who also care, who may challenge you, from your local community, as well as voices and stories from elsewhere. This is about connecting those cracks in the system, as to connect them makes them wider.

“The People’s Palace of Possibility, and projects like it, are suggesting a slightly different political role for the arts by creating spaces for democracy to happen.”

Perhaps when we (if we) think about the role of the arts in politics our first thought might be for spectacle, telling ‘untold stories’, or offering emotional connection to big issues. We might think of Extinction Rebellion’s striking Red Brigade making the front page of the newspaper, or Ken Loach’s latest film shedding light on injustice. But The People’s Palace of Possibility, and projects like it, are suggesting a slightly different political role for the arts by creating spaces for democracy to happen. To remove the veil from government buzz-phrases such as “meaningful engagement” and instead provide spaces that are playful and imaginative so citizens - not consumers - can dream with strangers and friends about how the world might be different, better. Strange spaces which invite us to step outside our lives for a while to see things from a different perspective, and which (at their best) make space for our anger and fear whilst also inviting play and joy. Maybe this kind of work can be one of the fissures which cracks apart this shitty system - it certainly needs to be broken.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.