Attacks by far right prove why events like Black On The Square are needed

Farage and Fox attacking celebrations of Black culture shows why they’re needed: we’re not remotely “postracial” yet.

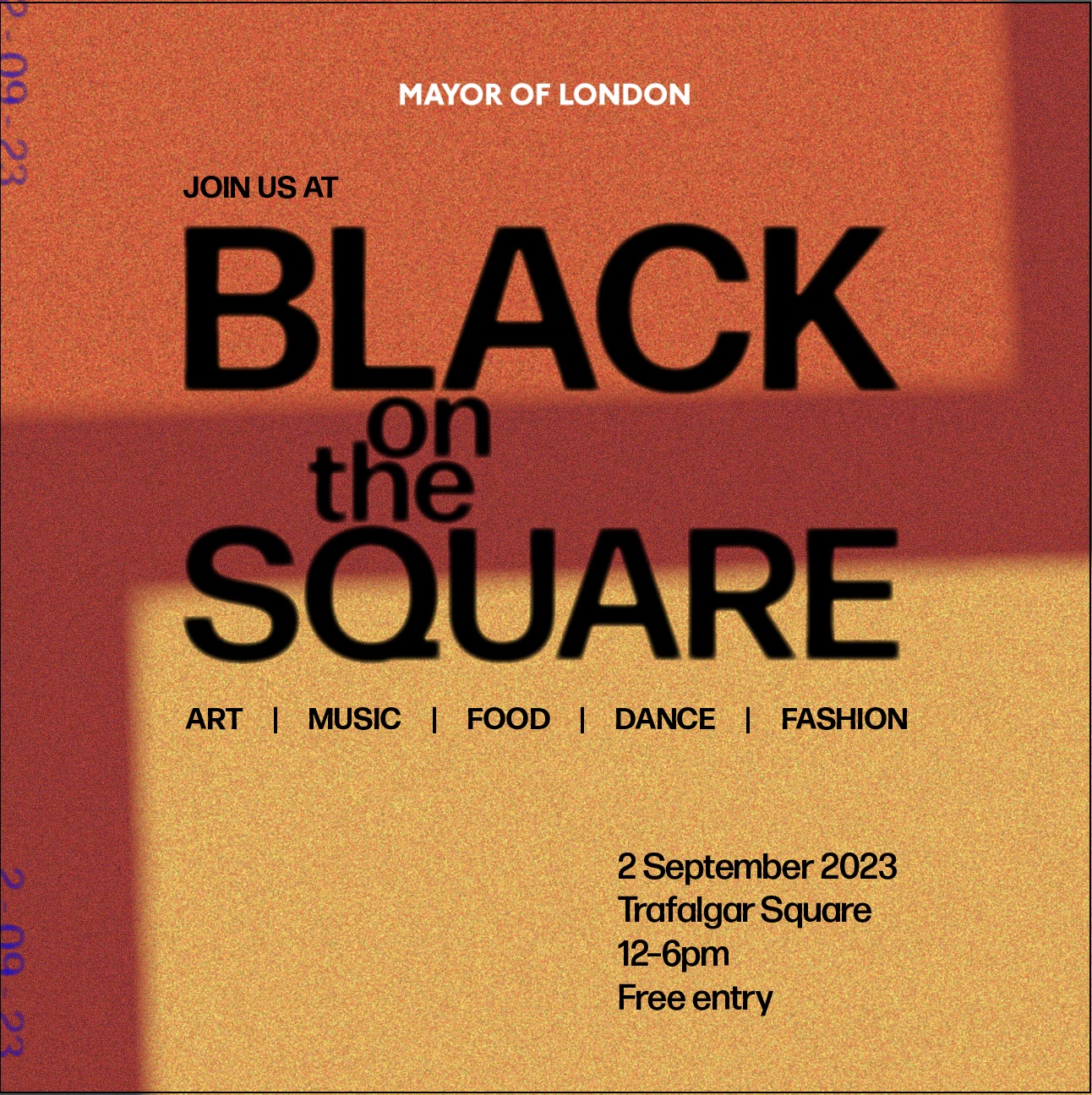

The Black on the Square event, taking place this Saturday in Trafalgar Square and set to repeat every year, will showcase a variety of music, dance, and delicious foods all spotlighting the creativity and vibrancy of the nation’s Black communities. It’s meant to bring Londoners together to honour and acknowledge so much so many of us hold dear.

And sure enough, it wasn’t long before professional stockers of division - starting with Nigel Farage and Laurence Fox - began attacking the event as “divisive”.

“Black on the Square is a special opportunity to launch a new annual celebratory event that will hopefully exist for generations to come,” says Amani Simpson, founder of youth organisation Aviard and one of eight Black on the Square community advisors.

“The event celebrates the talented Black minds in food, music, art, dance and more,” says journalist and event advisor, Kemi Alemoru. “London’s creative scene has so much to offer and this event will put that on display.”

Queue the affronted whines. Laurence Fox questioned on Twitter how Khan would feel if there was a “White on the square” event. Nigel Farage took to GB News to speculate what would happen “if somebody tried to organise a white culture day, an English culture day?” asked Nigel Farage earlier this month on GB News. He also labelled the event “bad news” and “horribly divisive”. Farage must have missed the past sixteen years of St George’s Day celebrations held by the Mayor. Last year, more than 20,000 people flocked to Trafalgar Square for the event designed specifically to commemorate “everything brilliant about England and being English”.

The problem is anti-Blackness – which fuels criticism of other Black-led events dedicated to celebrating African and Caribbean cultures in Britain.

“Black on the Square sits alongside other community programming events, showing the square is to be enjoyed by everyone,” says Alemoru.

What, then, seems to be the problem with Black on the Square in particular? The day isn’t exclusionary and there are a plethora of other festivities hosted at Trafalgar Square – Eid, Diwali, St Patrick’s Day, Vaisakhi, Lunar New Year, Chanukah, and Pride – representing a variety of the different cultures that make up Britain.

It doesn’t matter that there is a St George’s Day celebration, or other events spotlighting other cultures: either way, the critics would still raise the alarm over an event celebrating Black communities. The problem is anti-Blackness – which fuels criticism of other Black-led events dedicated to celebrating African and Caribbean cultures in Britain.

Each year, London’s Notting Hill Carnival is lambasted – demonised in a way other large-scale events are not. In 2020, Susan Hall, the Conservative mayoral candidate for London, labelled the Caribbean celebration “dangerous,” but in 2019 an investigation proved that rates of crime at Carnival are almost identical to Glastonbury, a festival which has been left out of the “crude culture war” and not subjected to similar levels of over-policing.

A recent freedom of information request from Liberty Investigates found that the Metropolitan police have only authorised baton rounds for Notting Hill Carnival and the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. Baton rounds are a colonial policing tactic: the rubber bullets were fired by the British in Northern Ireland in the 1970s.

The Met are not alone in their anti-Black policing tactics. Since 2006, Greater Manchester police have been banning people identified or “perceived” to be members of street gangs from Manchester’s Caribbean carnival – disproportionately affecting Black men and boys: a tactic recently described as “deeply racist”. Campaigners in Manchester have pointed out that this type of policing isn’t deployed at other similar size events in the city.

Racist attitudes toward Black on the Square are crudely disguised – sloppily hidden under faux concerns about ‘divisiveness’ and ‘fairness’. Although harder to spot than the overtly racist responses to other Black-led events, this type of outrage – so often a feature of the culture war – is a symptom of something sinister: the silencing of racism. How do you fight something that supposedly doesn’t exist? These seemingly mild critiques warp the realities of racism; there is no need for Fox’s sought after ‘white on the square’, because there is no systematic racialised oppression against white people. How can an event, like Black on the Square, be divisive when there is already division – the playing field is not equal.

In his disdain for the event Fox writes, “we are all just individuals. Each with our own unique stories, lives, experiences and views. Regardless of something so irrelevantly [sic] skin deep as colour of skin”. Another tweet critiquing the event, with upwards of two thousand likes, states: “Khan’s Black on the Square is divisive and racist. People are people, and their skin colour should not matter to anyone”.

Contempt for the event points towards a wider national inclination towards a belief in post-racial ideology. At first glance, this might seem like a good thing – don’t we want to inhabit a world beyond race and racism? But the reality is that most proclamations of ‘colour-blindness’ simply serve to bury discussions of racism and undermine the lived experiences of racialised people.

Consequently, any events, celebrations or works of art that assert that we are not, in fact, beyond the lived experiences of race – like Black on the Square, for example – are framed as a divisive attack on our ‘post-racial utopia’. Long fought-for efforts to take up space to celebrate the myriad experiences of Blackness are dismissed and the events themselves rendered superfluous at best – at worst, criminal.

Events like Black on the Square ought to be able to exist without being marred by thinly veiled racist backlash.

“It’s important to keep saying “we’re here,” says Adrian Gardner, inclusion and outreach producer at the Lyric Hammersmith Theatre, and another event advisor: pointing out that events like Black on the Square – and Carnival – reaffirm a sense of belonging in Britain for Black communities.

“It’s huge that this event is happening in the centre of the capital,” says Gardner. “I didn’t see a lot of events like this when I was growing up – large scale events celebrating blackness with all its intersections,” he says.

In the UK, the silencing – and even outright denial – of racism is not a difficult feat in the current political climate. In 2021, the government’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (the Sewell report) denied evidence of institutional racism in the UK. This is despite ample evidence to prove otherwise, and despite a review into one key institution - the Metropolitan Police - admitting the exact opposite just over a year later.

There are severe racial disparities in healthcare in the UK, such as Black women being four times more likely to die in childbirth than their white counterparts. Minoritised ethnic groups in Britain were most likely to die from Covid. The country’s judicial system is racially biased against Black and minoritised people, who are overrepresented in prisons in England and Wales. Last year, a landmark report from TUC found that almost half of Black and minority ethnic workers in the UK have faced racism at work – resulting in over 120,000 of these employees leaving their jobs as a direct result of the racism faced. In January, the United Nations warned against structural and systemic racism in the UK which jeopardises the rights of Black people in the country. This list could go on.

There are abundant examples disputing the myth of a post-racial Britain. Skin colour is not irrelevant. We’re not beyond race yet. And we still need - and will always need - joyful events that specifically celebrate Britain’s vibrant Black cultures. Spotlighting the exuberant creativity and talent of these communities in the face of structural inequalities is essential to prevent the pathologisation of Black experiences in the UK.

“Black joy is valid,” says Gardner. “Black people need the opportunity to dance and sing out loud whenever we can. It’s cathartic and healing,” he says.

“There is such joy and freedom in gathering to celebrate each other’s creativity,” says Alemoru. “The public spaces we share should be animated with people meeting, talking, dancing and enjoying the last of the summer together,” she says.

Events like Black on the Square ought to be able to exist without being marred by thinly veiled racist backlash; paradoxically denying the need for such a celebration, whilst mobilising racist tropes in order to do so. Reactions to Black on the Square make clear that extreme consideration must be taken when planning celebrations of racialised communities in Britain – how to prevent them from being tarnished by the culture war? However, this doesn’t take away from what Black on the Square will be – a vibrant celebration of talent, culture and creativity in Britain’s thriving Black communities.

Black on the Square takes place in Trafalgar Square, September 2, 12–6pm.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.