Ten tools for land justice

You have access to far, far more land than you think you do - but finding that out takes sleuthing. From slavery records to ancient tree maps, here is how to find out who owns what - and where you come in.

The land justice movement is growing. The old maxim, that land ownership equates to land stewardship has been shown wanting, as Britain’s biodiversity stats plummet to the ground. Meanwhile, the regulatory collapse of the environment - painfully illustrated by the state of our rivers and the degradation of our soils - increasingly necessitates a grassroots network of civic guardians to act in nature’s interests where official bodies have failed.

Which is to say: just about everywhere. We need a new model. And a new story to tell.

And to do that, we need tools. Over the past year the Right to Roam campaign has been using these tools to organise mass trespasses of the 92% of land with no right of access in England in order to challenge how we think about who is allowed to be in the countryside – and why. But they are just as useful for individuals as for campaigns. The land around us is subject to all kinds of laws, rights, protections, prohibitions and histories of which we are mostly only dimly aware, if at all. As a result, we can feel disempowered to intervene when we see wrongdoing: trees felled where they shouldn't be, important habitats threatened by the behaviour of landowners, and rights of access denied where they were once enshrined.

Illustrated below are some of the means we can empower ourselves to uncover stories about the land which surrounds us: how it came to be taken, how it has changed by those with the power to change it, and what condition it is in today.

Let’s go on a journey through one of Britain’s many private estates. The Charborough Estate comprises 14,000 acres of South Dorset. Its owners are the Drax family, including one of the wealthiest MPs in the country: full name – Richard Grosvenor Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax. Let’s see what we can find.

Ordnance Survey

First port of call is the trusty OS map. Now, you could pay out for an annual online subscription (currently £28.99). Or you could access it for free. On a non-mobile device, simply go to bing.com/maps, select the box in the top right corner (default setting: Road) and switch to Ordnance Survey. Voila. On a mobile device you can achieve the same by opening maps.the-hug.net in a fresh tab (note this has less depth than the Bing version). Below is the OS entry for the Charborough Estate.

What can we see? Like many estates of its kind, Charborough sits in ‘splendid isolation’. The A31 delineates its boundaries, the original turnpike road having been detoured away from the grounds in the mid 19th century. Along it runs the famous ‘longest wall in England’, built around the same time to keep the local people out and the ornamental deer in. There are no public rights of way. At some point or another, its broadleaf woodland has been exploited for commercial forestry, with only those woods nearest the house left intact to preserve an impression of timeless continuity. The deer park is just shy of the house itself. A great, phallic tower sits at the highest point to the southeast: the ultimate patriarchal symbol of dominion.

National Library of Scotland Online Maps

Were things always so? Sadly, very old maps are hard to come by without rootling around in museums and archives. If we could, we’d discover that Charborough was not always so isolated: in fact the estate covers what was, until the late mediaeval period, the flourishing village of Charborough. It benefitted estate owners to present their grounds as tabula rasa: continuity confers legitimacy.

However, we can easily access maps from the mid-19th century, using the nerd nirvana which is the National Library of Scotland’s online maps archive. Don’t be fooled: these cover all of Britain. Simply search for a location and select the historic map you’re most interested in (you may find it easier to select the Side by Side tab at the top, followed by Swipe On, allowing you to simultaneously see the contemporary and historic map). This is the ordnance survey record of the Charborough estate, taken in the late 19th century.

Here we get our first revelation. To the west of the main house is a public footpath running right to the heart of the estate, connecting it to the nearby village of Almer: perhaps a relic of the old mediaeval village on which the house is built. Yet, as we’ve seen, the contemporary OS map shows no such right of way.

Don’t Lose Your Way

Let’s investigate further, using the ‘Don’t Lose Your Way’ tool created by the Ramblers: a crowdsourced map comparing historical records with the current right of way network. Its initial findings suggest up to 49,000 miles of public rights of way are missing from the contemporary OS map: mysteriously vanished over time by hostile landowners whose sway - if not outright control - over local Parish councils has allowed them to manipulate the official record. We can see that, in fact, a whole raft of potential footpaths criss-cross the Charborough Estate. And, if there’s no evidence of their being revoked, you are well within your rights to use them: whether they’re present on the current OS map or not.

HMRC Tax Exempt Heritage Assets

Some landowners choose to operate so-called ‘permissive access’ on their land as part of a wheeze in which they receive capital tax relief (e.g. inheritance tax breaks) in exchange for what HMRC calls ‘the preservation of the national heritage for public benefit in private ownership’. Permissive rights can be revoked at any time, essentially allowing limited public access without the ‘risk’ of it ever being established as a true right: crumbs from the table proffered at the landowner’s discretion. Cynics might question whether this is truly a ‘national heritage’ being preserved, or simply a way in which potential public resources are channelled to protect the culture of an aristocratic elite…

Charborough doesn’t operate such schemes. But many estates do. You can check these on the HMRC ‘Tax-exempt heritage assets’ database. The ludicrous nature of some of these arrangements can be seen on this map of permissive paths on the Englefield Estate (owned, ironically by Richard Benyon, Minister for Access to Nature), in which the public is permitted to walk up Lord Benyon’s drive, gawp at the manor house in the distance, before being punted back across the edge of a desiccated field onto the A340. The worthwhile areas of the grounds all remain off limits. I feel more connected to my national heritage already.

DEFRA CAP Payments

But the most significant way the public directly pays for land ownership is through agricultural and environmental payments. How these are paid out is currently in flux, as the government transitions away from the European Union’s model of CAP payments. Nonetheless, we can get a snapshot of the sort of subsidies land owners have been receiving via the DEFRA CAP payments database. Note: records are only available for the years 2020 and 2021.

Finding the correct search entry can sometimes take a bit of sleuthing. Payments are given out under the name of the farm companies, which are usually different to estates or named individuals (for instance, the commercial arm of the 52,000 acre Badminton Estate is actually ‘Swangrove Farms’). Helpfully, Charborough Estate has made it simple: including the family surname in its commercial branding: ACF (Drax Farm). Here is its CAP entry for the year 2020.

We can see payments both to ACF Farms, the farming arm of the Estate, and to Jeremy Drax, the multi-millionaire property magnate (brother of Richard Drax). Public payments to the estate, and / or the family who own it, therefore totalled over £600,000 for a single year. The bulk of these were in the form of Basic Payments: the default payment then received by farmers who meet a minimal set of standards and criteria. Over £100,000 were for ‘Greening’, which stipulates specific ways the land should be used (or not used) for environmental benefit.

Were one to take the liberty of wandering our newly discovered footpath, one could of course start to see whether such stipulations are really being met on the ground and cross-reference them against the relevant guidelines in a given year.

DEFRA MAGIC Map

But there are many more things we can learn about what is supposed to be happening on land in exchange for public funding, bringing us to our most technical tool: the DEFRA MAGIC Map. This gives a ‘states-eye view’ of all the ways land interacts with governmental designations, licences, protections, and much more besides. One can look at heat maps of Raptor persecution sites, find habitat recordings for rare species, and check which areas are recorded as Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Here is just some of the data MAGIC records about the Charborough Estate.

The light brown and red hatchings show us areas of the estate recorded under different tiers of Countryside Stewardship Agreements, which (at least in theory) are payments to landowners undertaking work to improve the environment. Dark brown shows where licences have been granted to undertake any extensive tree felling, while light and dark green record areas covered by Woodland Grant Schemes. All this public money comes with specific guidelines of what should, and shouldn’t be happening in an area of land. Though oversight is poor: only a tiny proportion of the UK’s farms and estates are visited each year by inspectors (a government report in 2018 found a farm would, on average, be visited once every 200 years). All the more important for amateurs on the ground to understand what is happening to fill the breach.

Legacies of British Slave Ownership

If the public purse is one of the ways landowners get paid today, how did they come to own the land in the first place? In the case of many of Britain’s estates, the dark answer is: slavery. Charborough is no exception. In fact, the Drax family still owns its former slaving estate in Barbados – whose government is currently planning to pursue the family for reparations.

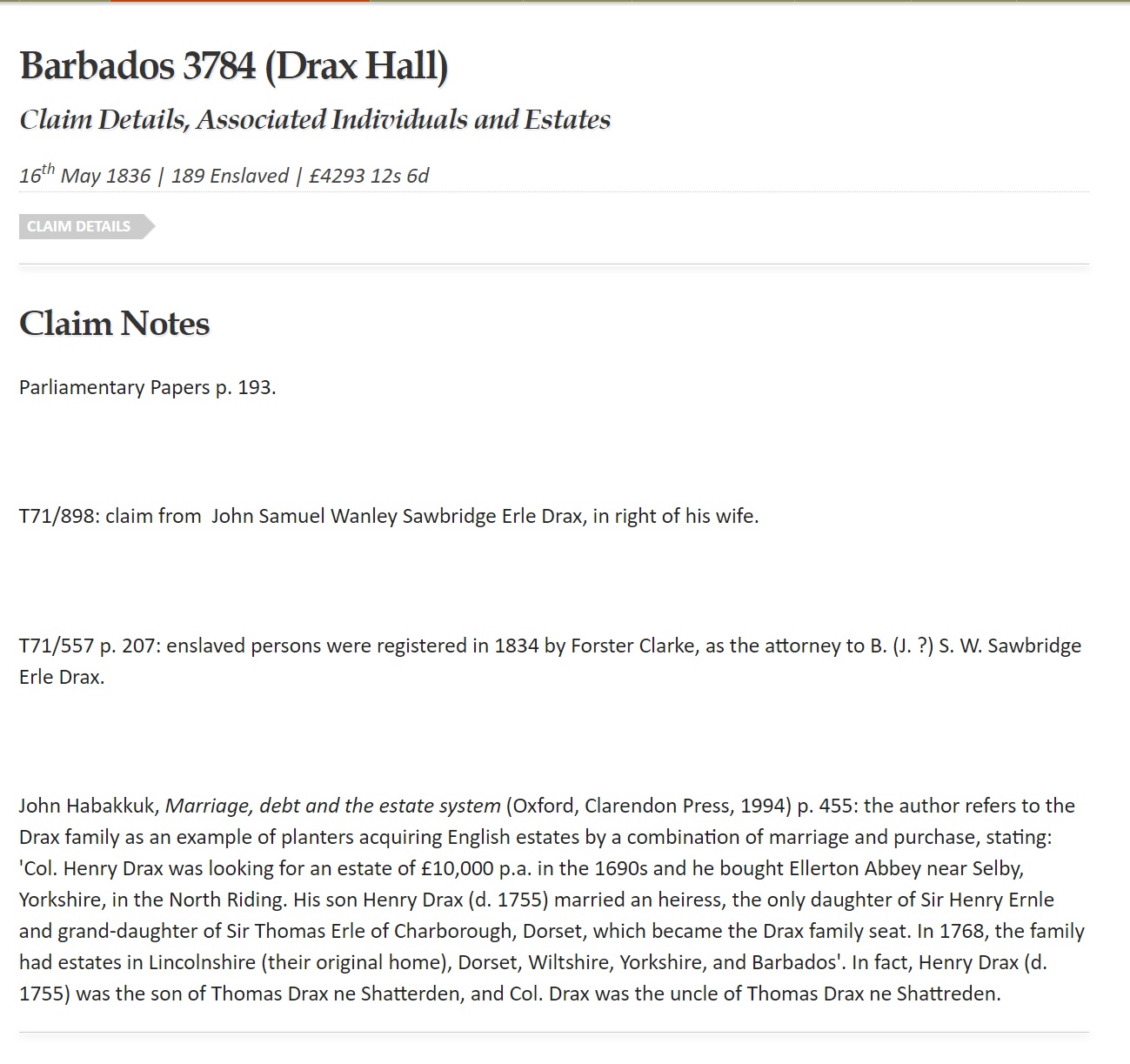

A landmark ‘Legacies of British Slave Ownership’ project by the UCL History department gives us insight into which parts of the UK profited from slavery. Using the compensation records from abolition (slave owners received around £20 million [worth approximately £17 billion today] for the loss of their ‘property’ – a debt only paid off by the UK government in 2015) the project gives a snapshot of beneficiaries of slave ownership across the country.

Unsurprisingly, the entry for the Drax lineage is extensive, enumerating a long history of slave interests. We can see that John Samuel Wanley Sawbridge Erle-Drax (later responsible for building that ‘longest wall in England’ to keep the commoners out) was awarded £4293 in compensation for the 189 slaves the family owned in Barbados. By contrast, the slaves were obliged to undertake another six to twelve years of further service as unpaid ‘apprentices’.

British Library Newspaper Archive

What was the impact of the exclosure slavery funded back in Britain? To find that out we can turn to the British Library Newspaper Archive, a digitised repository of numerous papers, magazines and journals from the mid-18th century. Wade through endless tedious accounts of massacring foxes on horseback, and a search of the Charborough Estate unveils some powerful stories, including numerous accounts of villagers fined and sentenced to hard labour for gathering wild flowers on the estate – just as they had for generations prior. Not, in fact, a crime at the time: not that that ever stopped the Victorian courts.

Account of a hunt on the Charborough Estate

Unfortunately the service isn’t free though if you live in London readers can access it directly from inside the British Library itself. But you can still search for records, and access a small sample, without subscribing.

Ancient Tree Inventory

But what other marvels of nature might be hidden behind Charborough’s walls? The Woodland Trust manages an ‘Ancient Tree Inventory’ listing notable trees of all kinds – as well as whether they’re accessible to the public. A small, positive flipside of Britain’s unbroken aristocratic landholding is that many private estates are particularly good locations to find ancient trees.

Which makes it all the more surprising that none are recorded at Charborough, likely due to the intensely private nature of the estate itself.

Yet recording such trees is an important part of protecting them: there are more laws protecting bus stops than trees which have been here for thousands of years. Without an active Tree Preservation Order, many are subject to the whims of whoever owns the land beneath them. As such, investigating and recording ancient and veteran trees for addition to the Ancient Tree Inventory is an important act of civic ecology. Applying for a Tree Preservation Order: even better. Friends of the Earth have produced a helpful guide on how to do this here.

Who Owns England (And Wales. And Scotland. And Norfolk. And… Oxford. And so on)

All this brings us to the vexed question of how we find out who owns the land itself. The reality in Britain is that it’s not so clear. Land owners have successfully resisted the numerous attempts to introduce a comprehensive, transparent, and accessible account of who owns what land across Britain, and so it has mostly fallen to citizen researchers to fill in the gaps. Our current estimates are that about 50% of the land in England is owned by 1% of its population, with old aristocratic families still owning well over a third of the land total (though since many such estates, including Charborough, are passed through family lines they have never been bought and sold, and thus evaded any recording in the Land Registry. The real number is likely to be considerably higher).

Documenting this are a number of ‘Who Owns…’ projects all over the country, providing a good (but very incomplete) map of land ownership. You can find links to these maps, as well as many other articles, tools and resources for investigating who owns land, and what is happening with it, on the Who Owns England website here.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.