The service charges trap

Residents in Urmston are locked in a bitter struggle with their management company. They are paying "extortionate fees", but have no idea where that money is going.

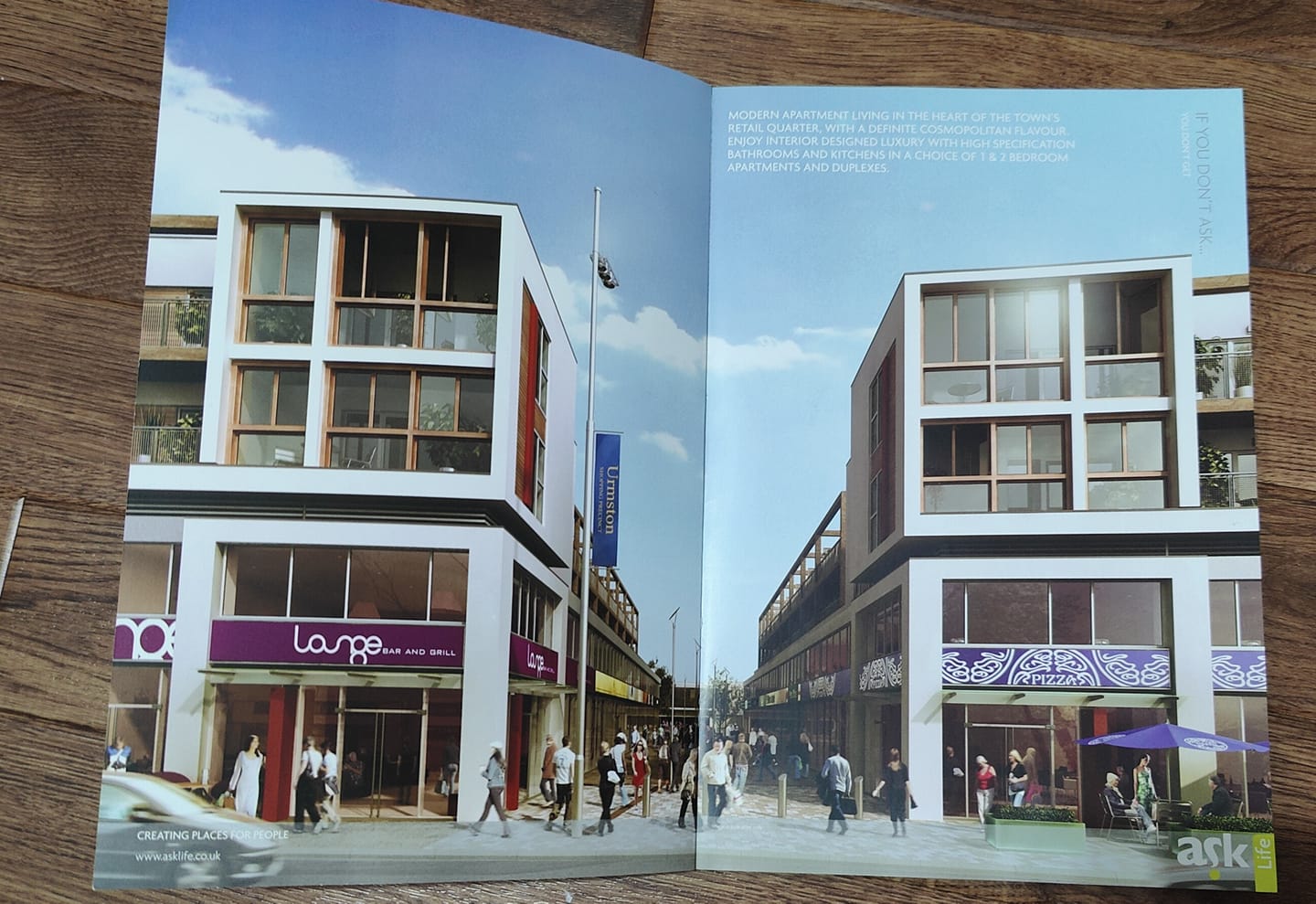

Jenny Greenway was 24 when she decided to buy her first flat. It was a cosy one-bedroom newbuild in the centre of Urmston, Manchester, set to be part of one of the town’s flagship developments. Being from Urmston, Jenny was excited – she had found the perfect flat that was within her price range, and just a stone's throw away from where she grew up. Ideal. “We camped out all night,” she tells The Lead.

It’s no surprise. Eden Square is a lovely development: the ground floor is completely commercial, home to a big Sainsbury’s, a Starbucks, and a gorgeous local coffee and wine bar, Lily’s at Eden, where revellers can go to sip espresso and hear live music performances. Locals chat to charity shop workers about their latest finds while others dip into Starbucks for a lunchtime coffee. There’s a real sense that the Square is more than just another shopping centre, it’s a community hub.

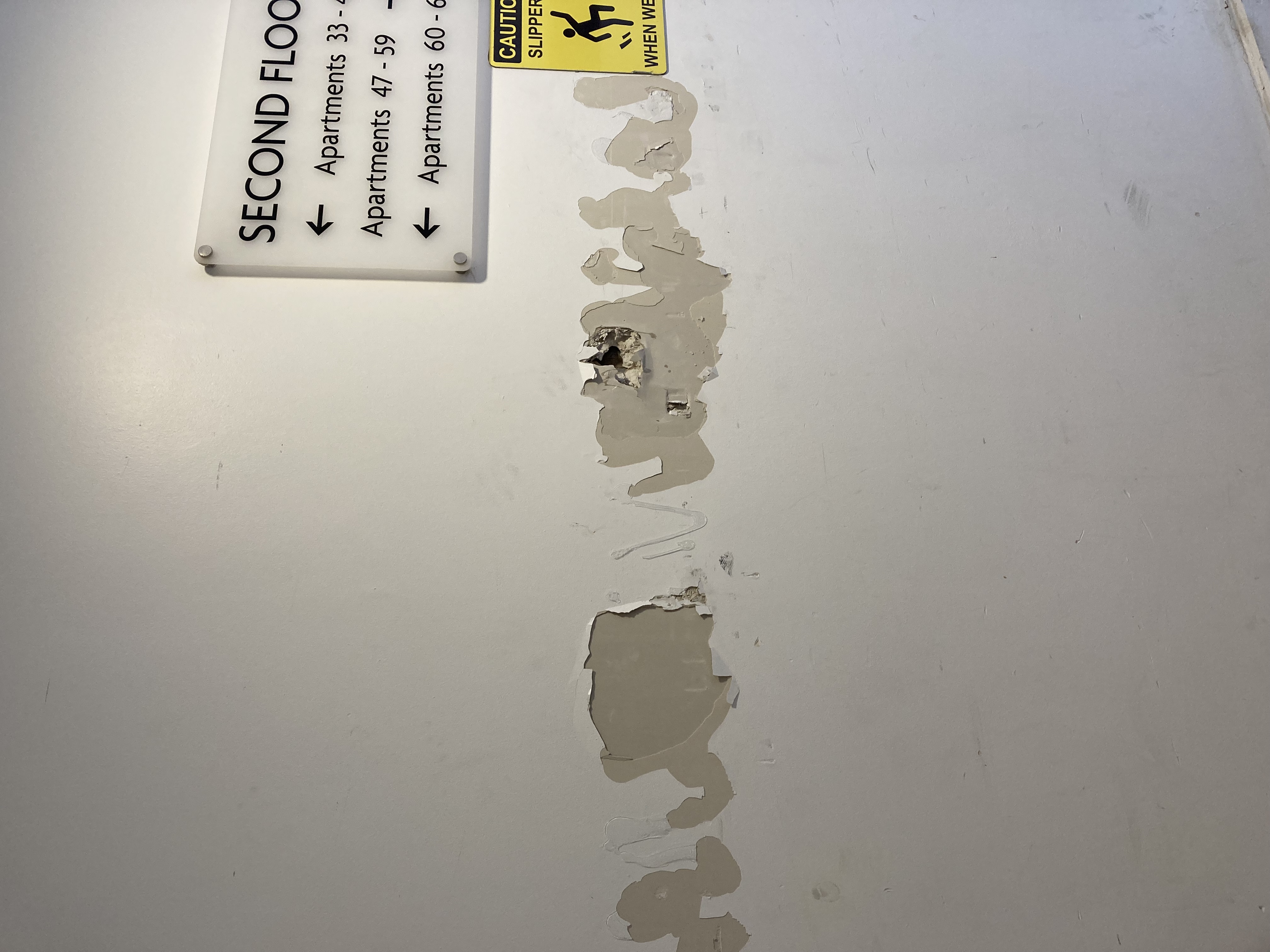

Scratch the surface, though, and things begin to literally fall apart.

Leaseholders like Jenny, who own leaseholds at the Eden Square development, say they are locked into a struggle with Residential Management Group (RMG), the property management company hired by the freehold owner to maintain the communal areas of the residential portion of the building. Leaseholders say they’re paying out extortionate fees despite work rarely being done to a high enough standard, or even at all. “They take out money for this work and that work, but we never really know what we’re getting,” says Jenny.

(Credit: Eden Square residents)

A stroll around the building shows you what they mean. There’s a CCTV camera that has “never been hooked up,” there are marks all over the walls where bins have been scraped along, carving out chunks of paint and plaster. One part of the floor, in front of a pair of shoddily fitted double doors, feels unstable, as though it's about to cave in. And it wouldn’t be the first time. Images on the resident’s Facebook group from 2019 show a huge hole in the ceiling caused by a leak, the walls are black with mould and a single mop bucket has been left under the leak by a concerned resident.

The outdoor areas aren’t much better. Communal doors are left unlocked, with no security to man the building, and the wooden pillars making up the balconies are visibly starting to rot. The white stone walls are washed green with algae and mould, patio tiles are mucky and grim, and the oak doors, now bleached by the sun, are a far cry from their original state.

A spokesperson for RMG said that the balconies and the structure of the building “are not under the management responsibilities of ourselves.”

“It’s being run into the ground,” says Jenny’s husband John Greenway, who also owns a flat in the development. “These issues are the result of years and years of degradation.” John and Jenny no longer live in the development, instead renting their properties out to tenants, but say they feel for the people still living there. “You’ve got families living there, you've got kids, you've got elderly people, you've got housing association people as well,” John continues. “They just need the place to be run properly. We're just treated so terribly.”

On top of leaky floors and unkempt communal areas, leaseholders find themselves constantly forking out more and more money, often with no idea what they’re actually paying for.

For Kay Kitchen, another leaseholder who lives off site but locally, one of the main issues is that when jobs aren’t completed in time, the cost falls on the leaseholder. “With no way of holding RMG to account, anything reported takes an age to be dealt with, to the point where you are forced to resolve it yourself or it costs twice as much,” she says.

One leaseholder who still lives at Eden Square, Ross Grant, decided to take matters into his own hands when he realised the decking on his balcony needed replacing. “I got a builder in myself and, to be fair, he did a really good job of it, but because one side of the building hadn’t been maintained, all of the joists underneath the original decking on that side were just rotted,” he tells us. This meant extra work for Ross’ builder, and led to the project going £50,000 over budget.“That’s because RMG didn't do any maintenance originally,” says Ross. “If they just came to weatherproof the beams like they were supposed to do, we wouldn't have had to spend that £50,000, and that's the case throughout the whole building. If they would come and fit new doors we wouldn't have ended up having to have a new floor fitted three times due to leaks.”

(Credit: Eden Square residents)

Ripped off

On top of leaky floors and unkempt communal areas, leaseholders find themselves constantly forking out more and more money, often with no idea what they’re actually paying for. On top of mortgage payments, ground rent and bills, leaseholders have to pay service charges to their property management company, in this case RMG. But Eden Square leaseholders find they are being charged thousands of pounds in extra charges on top of their quarterly service charge, because, John says “things are never delivered on budget” – and they feel shortchanged. “It means you can never plan, because you have no idea what bill is coming next,” says John.

Paul Malone bought his Eden Square apartment in August 2021. “I don't have as much insight into the problems with RMG as other residents, but I’d have to be blind not to notice the ongoing maintenance problems, and repair costs have grown,” he says. While he is starkly aware of the repair issues, like ongoing leaks and damage to floors and walls (“the list goes on,” he says), Paul’s main issue with RMG is the completely opaque charges he is being asked to pay.

“The invoices show balances that are owed but are impossible to verify,” says Paul. He lists off a barrage of unaccounted-for charges, including ones he has directly disputed with RMG, to no avail. “RMG’s ambiguity affects me financially,” he says. “I pay around £860 per month for my mortgage, bills and other essentials, and £220 per month for the service charge. I can just about manage without all the extras that RMG tries to force on us.”

“I’m just so sick of the blatant theft. Has £20,000 been spent on anything at all? On anything? Year after year after year, they charge an overspend, it’s madness.”

The problem is historical. Back in 2016, Jenny cancelled her direct debit to RMG after they “randomly” took £700 out of her account. When she asked why she had been charged so much, she says, the money was refunded. “I just don’t know what we’re paying for,” she says. “We're paying for window cleaners, and I don't think my balcony windows have ever been cleaned,” she says. Both Jenny and Paul note that, despite their service charge covering regular cleaners, they don’t seem to see any. “It’s not a cheap cost,” says Jenny, “RMG just passes it straight onto us, they just don't care.”

Most recently, John was told that residents are paying a “balancing charge” after an overspend of nearly £19,500 in the last year. Again, he wonders where the money has gone. “I’m just so sick of the blatant theft,” he says. “Has £20,000 been spent on anything at all? On anything? Year after year after year, they charge an overspend, it’s madness.”

The promise has not lived up to the reality (Credit: Eden Square residents)

The thing is, these leaseholders aren’t necessarily suggesting they don’t want to pay the fees, they just want something to show for it. “If you're paying that money and the building is absolutely spotless, there are no problems and you don't really have anything to complain about, that’s fine,” says John. “But the building is a wreck!” Ross agrees: “It's not some kind of entitlement from all our residents saying we just don't want to pay any money,” he says. “We want to pay – we just want to pay for quality service, and we don't want to be constantly ripped off.”

These complaints aren’t individual to Eden Square. A Facebook group called Residential Management Group rip off people's pockets has 4,300 members at the time of writing. It’s littered with complaints about unexplained payment increases, poor repairs and a lack of transparency. In a Times article from 2021, an unnamed former employee said that, although RMG claims that “things are going out to tender every year to get the best price,” they actually aren’t. “I knew what I was saying to them most of the time was lies and it’s not a nice position to be in,” they said.

The Eden Square leaseholders have even complained to the property ombudsman about their issues. Again, nothing: all they got was £175 between all 64 leaseholders. That’s £2.70 each. “It stops people from moving on in their lives,” says John. “It’s stopping people from being able to save and put money away for their pension and the things they want to do.”

The right to manage

Despite a constant stream of complaints being sent to the building’s landlord, PlantView (who employs RMG) "nothing is being done”, according to Ross. So, in an attempt to take control over the situation, Ross and another leaseholder, Kim Ramsbottom, organised a petition with the hopes of achieving the Right to Manage (RTM). RTM allows leaseholders of flats to take over the management of their building, as long as 51% are in favour of doing so. Ross and some of the others got to work acquiring signatures for a digital petition which would free them from the current chaos. In the end, they were only able to contact 72% of the 64 leaseholders in the building. Of them, every single one agreed.

That plan soon fizzled out when they realised they weren’t able to get the right to manage due to a clause in the law that states that the non-residential parts of the building must not exceed 25% of the total floor area. At Eden Square, the ground floor is 100% commercial, amounting to 45% of the total floor area, according to official floor plans. “It’s just rubbish and very unfair,” says Kim. “We should be more in control of who looks after our building, it’s our home at the end of the day.”

“People want to buy a normal flat in a normal Manchester suburb and live a normal life instead of having to deal with this crap. I just want to get on with the rest of my life.”

Harry Scoffin, a campaigner for the National Leasehold Campaign (NLC), says that not allowing leaseholders the right to manage leaves them open to abuse. “With more mixed-use developments sprouting, people literally cannot get RTM,” he says. “This is a big issue because when [freeholders and managing agents] know leaseholders can’t buy their freehold or get RTM, they can bring the service charge as high as they like.” While leaseholders can go to tribunal year in year out to challenge these costs, he says, it’s both time consuming and costly. “People have got families, jobs, lives,” says Scoffin. “They’ve not got time.”

Leaseholders, he says, become a “captive market,” like customers in an airport: putting up with extortionate prices because they can’t go elsewhere. They’re trapped.

(Credit: Eden Square residents)

A feudal system

The problems Eden Square leaseholders are facing are reflective of a much larger issue. England and Wales are the only countries that still use leasehold. In most other countries, the concept has been reformed, if not scrapped completely. “In a nutshell a leasehold is a form of tenure,” explains Paula Higgins, a leasehold expert at HomeOwners Alliance. “If you own a flat, you don't own the ground underneath, that belongs to the landlord, or the freeholder. Leaseholders have the right to live on the land for up to 999 years, but they have to pay ground rent to their freeholder in return.

For people buying flats, says Higgins, there isn’t really an alternative. “There’s something called commonhold, which means that when they build the flats, owners will already have a share of the freehold, but it isn’t really used,” she says. In this situation, the common parts of a building are jointly owned by the flat owners through a commonhold association, which also organises the management of the building.

Leasehold, Higgins says, is “deeply unfair”. Scoffin agrees: “You've just not got the autonomy, dignity and control that you would expect when you buy a home,” he says.

Leasehold is widely considered outdated and unfair. Both Lisa Nandy, Labour’s Shadow Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, and Conservative MP Sajid Javid, have previously labelled leasehold a “feudal” system. Michael Gove, the current Secretary of State of Levelling Up, has said that he wants to abolish the leasehold system, but changes to the law have been put off, and campaigners are waiting for any proposed changes to be implemented.

Until then, Eden Square residents will remain captive to the service charges and maintenance costs, waiting for the nightmare to end. “People want to buy a normal flat in a normal Manchester suburb and live a normal life instead of having to deal with this crap,” says John. "I just want to get on with the rest of my life.”

A spokesperson for RMG said: “We totally sympathise with the increased costs residents face to maintain, repair and insure their buildings. Whilst costs increase in line with inflation and further investment is needed as buildings get older we do all we can to ensure they get the best possible value. We procure contracts and services for their element of the building by a specialist procurement team which identifies providers based on their qualifications and competencies to complete works, their service record and ultimately the price. If any owner wants further information on the budgets and accounts issued our 24/7 team will assist.”

Take action

- Learn more about the National Leasehold Campaign

- Ask your MP to join the All Party Parliamentary Group on Leasehold Reform (APPG)

- Write to housing minister Michael Gove

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.