Non-birthing mums in same-sex couples discriminated and ignored

Women in same-sex relationships report experiencing homophobia and a lack of support from the healthcare services during their partner's pregnancy and postpartum.

Despite all of the well documented troubles of late, it’s generally assumed that the NHS is there for us all when we need it - including through pregnancy, birth and postpartum. You may also assume that LGBTQI couples receive the same treatment as hetero couples - but this isn’t always the case.

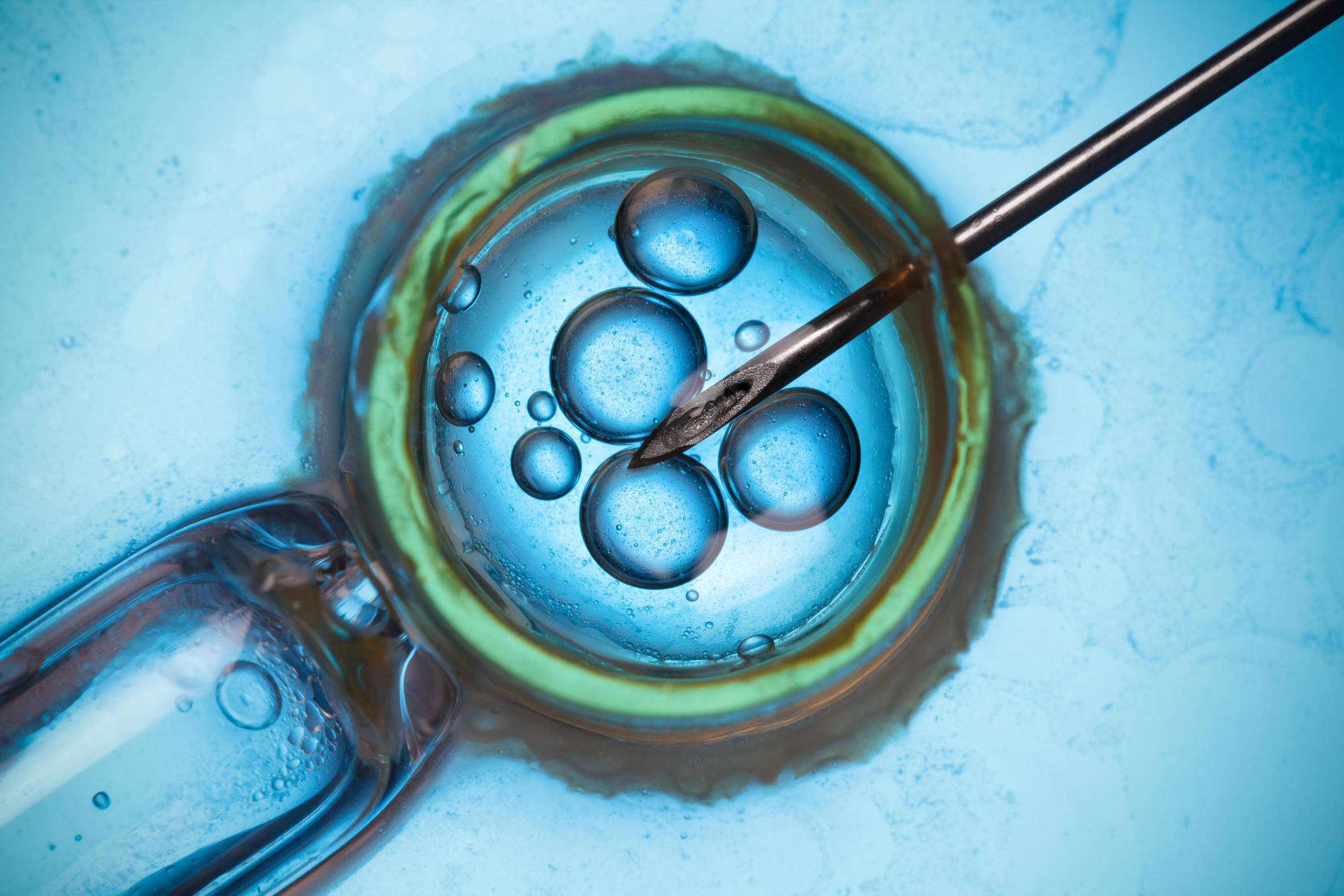

In fact, the inequality of reproduction for LGBTQ+ couples starts before a life has even been conceived. In England, the NHS will cover the cost of up to three IVF for heterosexual couples - depending on their postcode - after they’ve been trying for a baby naturally for two years – but same-sex female couples are required to self-fund up to 12 cycles of artificial insemination (AI) first, which can cost up to £1,600 per cycle. One in five Integrated Care Boards in England require up to 12 self-funded cycles of artificial insemination before offering any further support, which would mean they spend up to £25,000, according to a 2021 Stonewall survey.

Last year, the government said same-sex female couples would no longer have to do this, but there seems to have been little progress. For some same-sex female couples, this disparity – referred to as ‘the gay tax’ – is only the beginning.

After conception, pregnant people are offered a series of midwife appointments throughout their pregnancy. Becky, whose wife Nancy carried their son, says a lack of acknowledgement from medical professionals of previous pregnancies in their relationship retraumatised Nancy.

Becky went through seven rounds of IVF and three pregnancy losses prior to Nancy becoming pregnant through IVF. At her first midwife appointment, Nancy was told the couple’s previous pregnancies wouldn’t be recorded because they didn’t involve her body, Becky says.

“There was no place to put this on clinical notes, which meant she went through all of her prenatal experience with people consistently congratulating her on pregnancy,” she says. “And no mention of IVF or the three losses before it. We carry a lot of trauma and were very anxious; she would have benefited from recognition that this was our fourth pregnancy. If anything that can be learnt by NHS professionals it’s to take the relationship into account.”

One of the worst experiences, Becky says, was before Nancy got pregnant with their son, and Becky had to go into hospital for support during a miscarriage.

“Throughout this, my wife was referred to as a ‘friend’, which completely denied the grief she was experiencing because she was the mother,” she says.

When Becky later struggled to bond with her son due to her trauma, she went to her GP for support. Unlike gestational parents, there isn’t an established pathway of mental health services to support co-mothers.

Unequal access

A report published in October this year by Best Beginnings, based on interviews with 16 LGBTQ+ women who had conceived a child, found that non-gestational mothers lack access to appropriate perinatal mental health services.

The perinatal period – the first year after a baby is born – is generally a vulnerable time for parents, and the experiences of non-gestational mums can be different because they may have already had children themselves, says Mari Greenfield, a postdoctoral fellow at Kings College London.

"Some non-gestational mothers reported experiencing homophobia, even in their own families, from people who feel they shouldn’t have become parents."

“Some may have birth trauma that could impact how they feel about their partner’s pregnancy and birth and the support they’re able to provide and need,” she adds.

Rebecca has two children, both of whom are both genetically hers, but were carried by her wife through pregnancy. She and her wife went through a private IVF clinic, where Rebecca says they were treated by staff who provided a positive experience for them both. But once the NHS appointments started, Rebecca started to feel sidelined.

“I didn’t feel like I was a part of the process,” she says. “I didn’t feel like I was treated like a mother, I felt like I was treated like a dad. It was subtleties, rather than anything overtly said or done. I felt like I shouldn’t be there, or wasn’t necessary.”

Rebecca says she was repeatedly ignored in antenatal appointments, and was often asked if she was her wife’s sister.

“The biggest issue was the heteronormativity around paperwork and documentation; it wasn’t made for families like ours,” she says.

When their second child was born, he became unwell and had to spend some time in the ICU.

“Some of the nurses were great and included us both in the conversation, but others talked to my wife and didn’t look at me or engage me in the conversation,” she says. “It’s an attitude of ‘Who’s the real mother?’”

It’s important that medical professionals recognise that they might be caring for a family where both people have pursued pregnancy or been pregnant, says Zoe Darwin, a co-mother, who has researched non-gestational mothers’ experiences of perinatal depression and anxiety.

She found parallels between co-mothers and dads, such as concerns around whether people can access mental health support themselves without taking focus away from their partners, and how some people feel they’ve lacked a parenting role model they can relate to.

Some non-gestational mothers reported experiencing homophobia, even in their own families, from people who feel they shouldn’t have become parents. And some said they felt additional pressure to look like they were coping once the baby was born.

“It’s seen as letting the side down. You might be the only queer family someone knows and if people see you struggling, that might contribute towards their impressions of LGBTQ families, “ Darwin says.

Experts argue that there needs to be more training to help medical professionals understand the importance of being more inclusive. At the moment, Darwin says, health professionals don’t often ask about sexuality or gender, and some research suggests that heteronormative assumptions in the care system might contribute to peoples’ vulnerability.

Becky - who was particularly hurt when, after asking the nurse a question after the birth, the nurse told her she needed to speak to the ‘real’ mum - says staff training around LGBT inclusivity would go a long way to preventing moments like this.

“None of this is hard to get right; just don’t presume two women aren’t in a relationship together,” she says.

Greenfield says she has also heard from many LGBTQ+ parents that professionals assume the non-gestational co-mother is a sister – and even, in one case, the grandmother.

“It’s frustrating and invalidating for people, but they also carry a fear that it might happen even if it doesn’t, which also has an impact,” she says.

“Good, inclusive care can be a really protective factor for perinatal mental health.”

Not only is a partner’s mental health a big part of the gestational mothers’ mental health following birth, but research also shows that a partners’ mental health after birth can affect how they bond with their new baby, which can then contribute to poorer developmental outcomes for the baby later in life.

Feeding inequality

Current NHS training isn’t equipping midwives and obstetricians to feel confident around what language to use, Greenfield says – nor is it training them to deal with specific practicalities, such as helping to induce lactation in non-gestational co-mothers.

The Best Beginnings report also states that non-gestational parents who wish to breast or chest feed their babies do not have adequate support, and that a lack of knowledge about co-feeding poses a risk for newborn babies.

“My wife carried our first, and I struggled because of discrimination. The doctor didn’t want to deal with me because I wasn’t the ‘real’ mum."

Greenfield studied the experiences of two lesbian non-gestational mothers whose breastfeeding intentions were disrupted by the postnatal ward visitor restrictions during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Both had planned to breastfeed and had taken steps to ensure they were lactating, but ‘heterosexist’ restrictions for partners after birth impacted this, Greenfield says.

“Co-lactating isn’t something the NHS is able to really support,” she says. “This can be quite dangerous for a baby. Women’s experience is that midwives are supportive in saying it’s a good idea but they really lack knowledge.

“Quite often, women will need to be prescribed medicines to induce lactation, and they shouldn’t have to go private in order to receive an adequate service, but there’s no support.”

While the prospect of a clear pathway of support for non-gestational co-mothers’ mental health is unclear, there’s also little research being done to investigate the scale or consequences of what appears to be a widespread experience of being excluded and retraumatised through the perinatal period.

But it’s very difficult to get funding in this area, Greenfield says, because of a “combination of scepticism and homophobia”.

Another problem is that data showing disparities of care isn’t collected, says Laura-Rose Thorogood, founder and director of support group LGBT Mummies.

“We don’t know what the LGBT journeys look like, so without knowing the inequalities and implications, we’re not giving the care that’s needed,” she says.

Anecdotally, Thorogood – who has two children with her wife – hears that a lot of non-gestational mothers can feel a ‘genetic loss’, where they struggle to accept that they aren’t the parent who is carrying and birthing their child.

“LGBTQ mums can feel ashamed and less-than,” she says. “They’re often invalidated, not addressed, and seen as a third wheel. And their mental health isn’t considered.

“My wife carried our first, and I struggled because of discrimination. The doctor didn’t want to deal with me because I wasn’t the ‘real’ mum. It had serious implications for my mental health, our relationship, my bond with my daughter and my relationships with family and friends.”

There is some hope that services could improve how they support and engage with non-gestational mothers. Within the next year or so, the NHS has plans to offer maternal mental health services for pregnant and postpartum women for whom there's previously been a gap in treatment - including those dealing with infertility, baby loss and birth trauma. This will also include trialling support for dads, Darwin says.

“Maternal mental health services will aim to meet the needs of parents who were falling into gaps and weren’t necessarily eligible for specialist perinatal mental health,” Darwin says.

“In England, pregnant people have routine mental health assessments, and there are calls to extend this to co-parents. Maternity services aren’t doing this yet, but specialist maternal and perinatal mental health services have an ambition to bring this in,” she adds.

Darwin predicts that same-sex co-parents could start to be signposted to their GP by midwives who see that they’re struggling.

“This shifts the conversation around who might be seen in the service away from someone who is pregnant or has given birth. It’s not necessarily about improving existing services, but how we recognise all these unmet needs.”

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.