“It’s life or death”: How racism shapes medical treatment

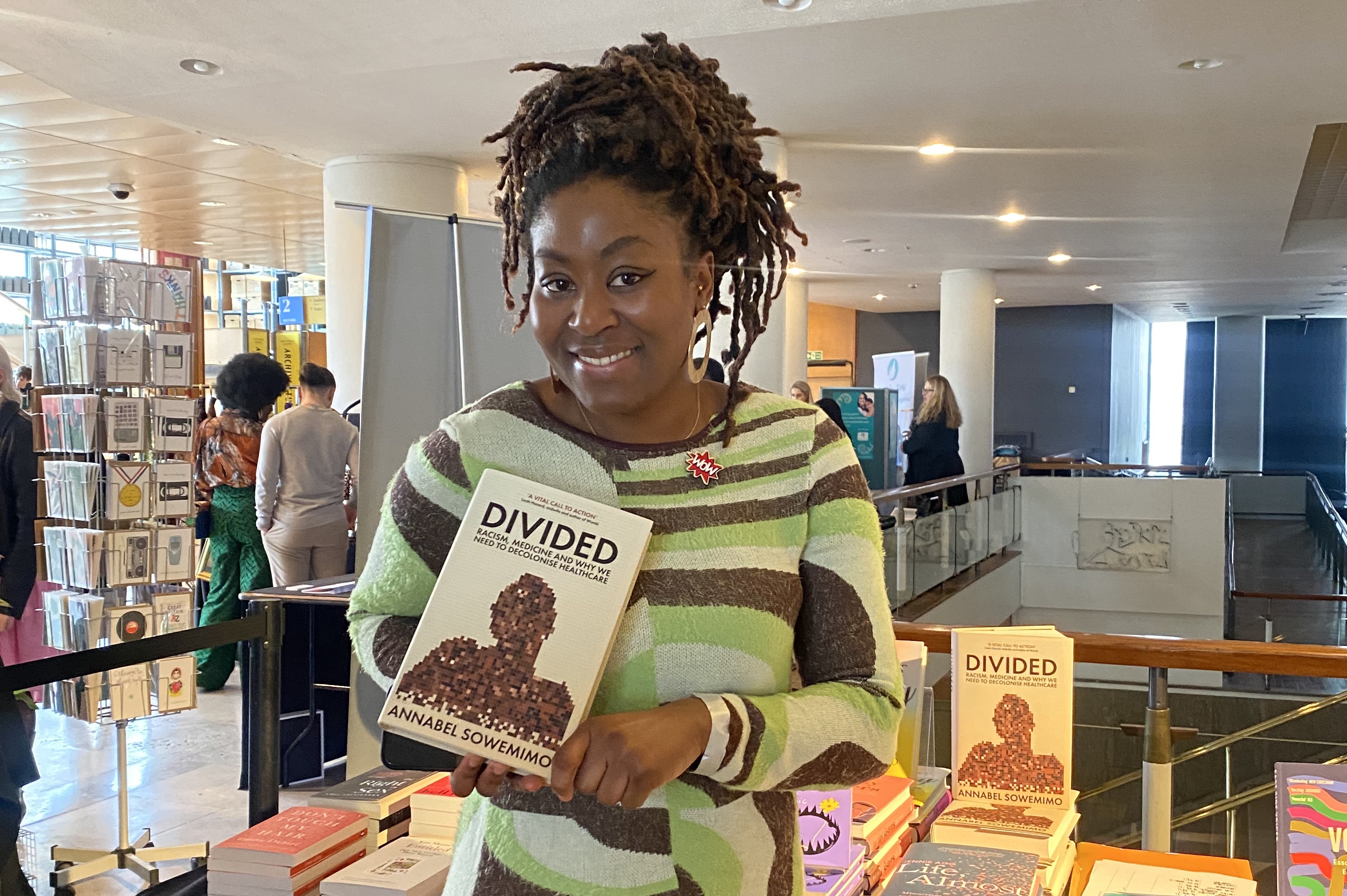

From the myths about Black people not feeling pain, to racist technology that discriminates against ethnic minorities, Dr Annabel Sowemimo's new book explores the urgent need to decolonise healthcare.

Medicine is in Dr Annabel Sowemimo’s blood. Her grandmother came to the UK from Nigeria in the 1940s in response to the government’s pleas to the Commonwealth to help rebuild Britain after the war. She got a job as a nursing auxiliary and became one of the thousands of migrants to work in the fledgling NHS. They were the foundations of the service - and yet, even at its inception, the NHS was not built with people like them in mind.

“They were an afterthought," Sowemimo tells The Lead. “There was never a plan for these people to actually use the health service they were building. My grandma told me how sick people were - her friends and colleagues and people she lived with. Their accommodation was often overcrowded, they were exposed to tuberculosis, there was no kind of occupational health. They came here to provide healthcare for this country, but it was very difficult for those same people to actually make use of this system.”

The roots of racism in healthcare run deep and reach further than most of us could imagine. And, Sowemimo argues, these systemic inequalities are by design. Healthcare spaces in the UK have a chronic lack of diversity and systemic biases that filter through at every level - from seeing a GP, to accessing mental healthcare, to using an app to track your menstrual cycle. We saw these inequalities play out in stark and tragic terms during the COVID pandemic with disproportionate mortality rates in ethnic minority groups, but this is not a new problem.

In her debut book Divided, Sowemimo unravels the colonial roots of modern medicine, the hidden histories of racism, and the damaging myths that are still believed today. These myths include the incorrect assumption that Black skin is more resilient and that Black people do not get skin cancer, an idea Sowemimo identifies as a “significant barrier” to improving diagnosis and treatment of skin cancers in patients with darker skin. She points to the famous case of Bob Marley’s fatal melanoma diagnosis as an example of the delays and underestimations that can occur in Black patients. “Far less time has been devoted to treating Black skin than has been to pathologising it,” she writes. “Despite Marley being a musical legend, his untimely death from skin cancer has still failed to raise awareness of skin cancers most prevalent in those of darker skin or a greater focus on research into its causes.”

In another chapter, Sowemimo explores the fallacy that Black people don’t experience pain, or at least have a higher threshold. She writes: “Racialised tropes of how people respond to pain can even lead to shocking discrepancies in the administration of pain relief today.” Studies - mostly in the US - have revealed that doctors are less willing to prescribe pain relief to Black patients, and that white patients more frequently receive stronger medication. This example will likely resonate strongly with sickle cell patients in the UK, many of whom have reported being disbelieved by healthcare professionals, denied pain relief even when they are in agony, or being “treated like criminals”.

Racist healthcare practices have real-life impacts

The book is part of a long-overdue process of reassessment by the medical establishment. The publishers, Wellcome Collection - a global medical research foundation housed within a museum and library that connects medicine with art and history - publicly acknowledged that it had “perpetuated racism” in June 2020, and a statement in August last year admitted “insufficient progress” had been made on anti-racism. In November, the institution announced it was to close its Medicine Man exhibition after 15 years, labelling it “racist, sexist and ableist”.

"People need a better handle on how eugenics continues to shape our current scientific practice." (Picture: Annabel Sowemimo)

To analyse the real-life impacts of racist healthcare practices, Sowemino recounts her own experiences - both as a sexual and reproductive health registrar in the NHS and as a patient - with searing honesty, and calls for the acknowledgement of past and current failings, as well as systemic change.

“We have to go back to make sure we don't continue doing the same thing. We have to understand history, how we've ended up here, so that we don't replicate the same kinds of behaviour,” Sowemimo says. She points to the example of pulse oximeters - the machines that measure the level of oxygen in your blood. After the pandemic, it was widely acknowledged that the machines were not accurate or effective in people with darker skin - and that using them was therefore dangerous. However, many people - including Sowemimo - had highlighted this problem long before COVID hit.

“The first paper that was published about the pulse oximeter being less effective in darker skin was almost 15 years ago,” says Sowemimo. “Yet, these machines were still being used as though they were accurate for everyone all that time.”

To understand why this was allowed to happen for so long, Sowemimo says, you have to understand how racism operates. She says this isn’t simply a case of an oversight or a design flaw, but that it speaks volumes about who matters and who does not. “There are multiple things going on here,” she explains. “First of all, someone designed a device - a major intervention used across Africa, Asia and Europe - and it wasn't checked on enough people to be able to say ‘this is working’ across society. Then, when we did realise, after several years of widespread use, that it wasn't working in Black and brown people, it took another 15 years for anybody to say this is actually a serious issue. Nobody asked - how big is this margin of error? Or - could it really be killing people? And then, when we had a global respiratory pandemic, and we were handing out pulse oximeters like lollipops, at no point did anybody publicly highlight this known issue. These are not minor problems, these things are literally life and death.”

The data on racial inequalities in medicine presents a bleak, and concerning, picture. In the UK, Black women are four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Black people are more than a third less likely than white people to be diagnosed with cancer via screening. Black and Asian people have to wait up to six weeks longer for a cancer diagnosis than white people. These are just a handful of examples.

Research published in October 2022 by the Black Equality Organisation revealed that 65% of Black Britons have reported being discriminated against by a healthcare professional because of their race, a figure that rises to 75% among those aged 18-34. Meanwhile, a damning report from February last year by the NHS Race and Health Observatory found “vast” and “widespread” inequity in every aspect of healthcare it reviewed, and concluded the health of millions of patients was at risk. The study’s authors concluded that “Ethnic inequalities in health outcomes are evident at every stage throughout the life course, from birth to death.”

For Sowemimo, the heart of so many of these problems is a significant lack of “race science literacy”. She wants more people to understand where these damaging ideas came from, how they developed, and the many ways they impact modern medicine - rather than being perceived as historic atrocities that happened long ago.

“When people think about race science or eugenics, we often get stuck in Nazi Germany - this concept that these horrible things were done by a handful of fringe scientists, and that nobody was subscribing to it,” Sowemimo says. “But people need a better handle on how eugenics continues to shape our current scientific practice.

“Healthtech is really important, it can do a lot of good, but also, it can also replicate a lot of the same models that we have in society.”

“A good example of this is how we treated elderly or disabled people during the pandemic. How the narrative against lockdowns became about ‘survival of the fittest’, and how people with underlying health conditions are disposable because they are ‘less useful to society’. Similarly, I spoke to many Black health professionals who noticed COVID wards were disproportionately staffed by Black and brown nurses and doctors.” Sowemimo believes these decisions about who would be on the frontlines of the crisis - who would be put at the highest levels of risk - was related to the same considerations about the disposability of minority groups. “It was abhorrent. And that kind of thinking really is the heartbeat of eugenics theory.”

Sowemimo says it’s also important to look forward. The future of healthcare lies in technology, the AI systems that will come to automate medical processes, the machines that will diagnose life-threatening conditions, the apps that will store and analyse our medical data. For Sowemimo, there is so much positive potential in healthtech developments - from streamlining complex diagnostic processes to reaching communities that struggle with language barriers or accessibility issues, but there are also many red flags to be wary of.

“Healthtech is really important, it can do a lot of good, but also, it can also replicate a lot of the same models that we have in society,” she says. “So this idea that we are going to suddenly start improving health inequalities just by being innovative with technology, it's way too optimistic. We still have to do the work.

“One worry is that by using things like algorithms in diagnosis, for example, you could end up accidentally discriminating at scale. Where before, discrimination and bias would happen on an individual scale, if you become reliant on a biased algorithm, that discrimination can impact millions of people every single day. This is what is happening. And a lot of these apps aren't tested, or impact assessed, until much later on, when people realise it's not working. So we have to be a lot more vigilant and questioning of some of these developments.”

Divided: Racism, Medicine and Why We Need to Decolonise Healthcare by Annabel Sowemimo is published by Wellcome Collection/Profile Books. Sowemimo will be at the Wellcome Collection on April 27, 2023 in facilitated conversation on racism, medicine and the urgent need to decolonise healthcare. Book your free tickets here.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.