"Do it. Pay it." Andy Burnham warns against delaying contaminated blood compensation

Ahead of the inquiry report next week, The Greater Manchester Mayor and longtime campaigner for victims of the scandal says the "typical Whitehall reaction" of delaying action for fear of consequences has cost lives, and calls for a "duty of candour" for civil servants.

Victims of the contaminated blood scandal should be paid compensation no matter the sum, the Mayor of Greater Manchester and former Health Secretary, Andy Burnham has told The Lead.

Burnham—who has spent years campaigning for those impacted by infected blood—spoke to us as survivors nervously await the findings from the six-year-long inquiry into the scandal on Monday 20 May.

The Manchester mayor has called for the government and future governments to pay those who have had their lives blighted by one of the largest treatment scandals in NHS history. “It has to be paid,” he told The Lead. “Stop compounding the harm. Do it. Pay it.”

Almost 30,000 people were given blood transfusions or products that had been contaminated with Hepatitis C and HIV in the 1970s and 80s. The contamination came as a result of supplies imported from the US, which had been harvested from prisoners and vulnerable people. Thousands, including young children suffering from haemophilia or other blood disorders, were injected with the contaminated blood products. More than 3,000 people have since died.

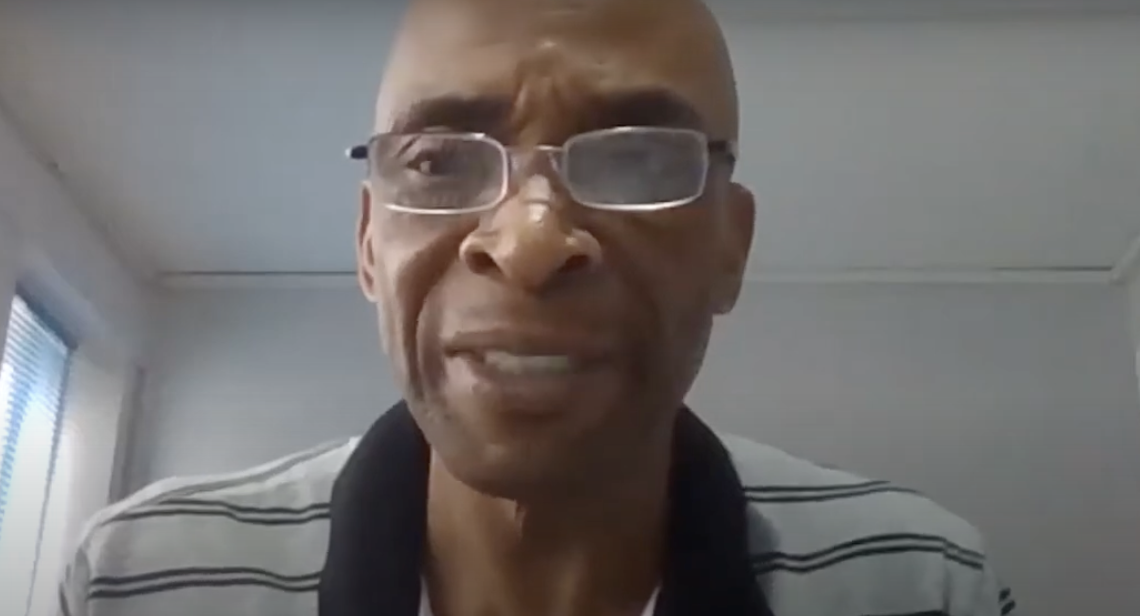

Jason Evans, founder of campaign group Factor 8, has spoken about he and his family’s experience after his father died of AIDS as a result of being given contaminated blood.

“Your immune system has been destroyed, [AIDS] just wreaks absolute havoc on the body”, he told The Lead. “It was just the absolute worst. Such a horrendous way to go. And then you add on top of that all of the stigma, how difficult it is to hide having AIDS.

“I look at photos of my dad and I can see the change of him from a young man to looking completely decrepit and on death's door by the age of 31. It's pretty horrible to look back and see that change, which was replicated through so many families.”

The search for justice has been long—and for decades, fruitless. Ministers in successive governments have held the line that patients were given the “best available treatment” and that clinicians did not have the knowledge to prevent the tragedy.

But years of tireless work from campaigners and survivors have finally opened up a path to justice. Though we are yet to know its conclusions, the Chair of the inquiry, Sir Brian Langstaff, has already said in an interim report that “wrongs were done at individual, collective and systemic levels”. Throughout the probe, there was clear evidence that warnings had been issued to government officials as early as the 1970s. Documents had allegedly been destroyed, whistleblowers ignored, and victims knowingly injected with diseases.

The significance of Monday’s conclusions for the victims can not be understated. Evans said they can not “consider the possibility that we will get anything other than the full truth”.

“Monday, more than anything, is about bringing some form of psychological closure. Not just to me but to everyone impacted by this for decades. It's just this lingering shadow of pain, frustration, anger, mystery and conspiracy. There's almost an endless list of words I could use to describe it. And it is just this cloud over your life constantly: the questions of why and how.”

“Monday really marks the final chapter on that,” he added. “There's still the question of compensation, redress and accountability. But the truth - that is the part that will be delivered on Monday.”

Burnham said the key question he will be asking is how the government were able to maintain that no one knew the producers were contaminated. “How can we have an official line for decades that turns out to be a lie?” he asked. “Nothing can convince me that the inquiry won't find that. It's a lie that was developed to protect the state from liability. The idea that ‘nobody was knowingly given unsafe products’, well, it's just not true. They were knowingly given unsafe products.”

"Simply tell the truth at the first time of asking"

So far, not a single individual has faced prosecution for the catastrophe. It wasn’t until October 2022 that victims were finally offered compensation of £100,000 each. By the end of that month a total of £400m was paid out, but only one in three families were eligible for the payment.

The death of loved ones was not the only thing victims had to endure. Survivors have spoken about the shame they were subject to after they or their family member was diagnosed with HIV, at a time when misinformation about the illness was rife. Others talk about years of trauma, lost experiences and lost earnings after losing parents, spouses, brothers and sisters. Others say the six-decade-long fight for justice has left them emotionally and mentally spent.

Allowing the scandal to drag on for so many years has made the true cost of compensation “incalculable”, according to Burnham. “It’s had a secondary re-traumatising effect…The cost of this is just incalculable really, because you're talking about tens of thousands of people who've felt the knock-on impact. What they've been through is just beyond what anybody should ever be put through. Yet the state has done that.”

The scale of the tragedy has silenced the government. For years, successive administrations have avoided culpability. In January last year, the government’s lawyers sat in front of the inquiry and acknowledged there was a “moral case for compensation to be made”—but they stopped short of acknowledging specific failings, much to the dismay of all the victims watching.

Burnham compared the longevity of the blood scandal to other recent cases of corporate and institutional cover-ups, including the Horizon IT scandal, Grenfell and Hillsborough. In all cases, Burnham said, the government took far too long to act for fear of the consequences.

It’s a “typical Whitehall reaction,” Burnham explained, which is to “limit financial liability and exposure.”

“And they're still in that mentality,” he added. “It’s so entrenched. That's where they still are and they can't get out of it. But that's how they all lined up behind the lie.”

For Burnham, the inquiry’s conclusions will be indicative of larger lessons for parliament to learn: “The bigger question for me is: how does the country keep doing this, [allowing] these big injustices that just go on for decades? Why doesn't Parliament correct them earlier?”

“A very significant thing would be a full and far-reaching duty of candour on all public servants. Simply tell the truth at the first time of asking. If they did that, it’s not just the financial cost that will be lower, but the human cost too.”

Evans said whatever happens on Monday, victims won’t be celebrating: “There will be a lot of ghosts in there on Monday, put it that way. And that’s just the saddest party really. Those who should have been given the truth just didn't see it. I think the only solace I can take from it all is that we honoured their memories by fighting for the truth and the truth going down on the record.”

“That scene that so many campaigns dream of - holding a banner and cheering ‘we did it’, that doesn't happen in our campaign. It's all too late,” he explained. “When you're describing a story or a campaign you want it to have some kind of redemption at the end or some kind of happy ending. I just don’t see it. But I'm glad at least there will be some form of psychological closure and redress.”

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.