Canal boaters “facing homelessness” as fees shoot up 75%

Britain’s boating community once moved according to the season; now, they are being forced from our rivers and canals by extortionate charges.

Bounding from concrete to metal, I land on Lisa Newell's narrowboat, the second boat in the flotilla. We only met moments before, but I’m welcomed aboard with familiarity. We slowly cast off toward the Canal & River Trust [CaRT] head offices. Water catches light in dapples, and the chants of united boaters become clear: “One Licence – One Fee”. It’s the 26th November 2023 at the National Bargee & Travellers Association [NBTA] protest in Birmingham, the heart of the canal system. All boaters here are against announced surcharges from CaRT aimed at continuous cruisers [CCers].

Nomadic boaters face eviction and cultural eradication. This historic lifestyle has been a part of Britain’s landscape for three hundred years, but new fees set by CaRT, a charitable organisation assigned to protect canal heritage, may cause many nomadic boaters to alter or leave their itinerant way of life - some by force.

“It’s discrimination, and if something isn't done at a high level, we will have people homeless,” says Newell, a CCer of seven years.

The surcharges came into effect on April 1st. From now on, an additional fee will be applied to boaters without a permanent mooring, such as a marina. Wide-beam boats face even higher charges. The base licence fee will increase over inflation while discounts are phased out and essential services such as sewage disposal cut. At the end of this period, 2029, some boaters will be paying 75% more than they are now.

These new costs follow an overarching fee rise of 13% between 2022 and 2023. The fear is that by ushering nomadic boaters into marinas and off the canal system, CaRT will sell these publicly accessible lands, motivated by profit.

Newell thinks the policy seems illogical in its basic principle: “It’s like saying; if you park your car on the road and not in the driveway, you use the road more, so you have to pay more road tax.”

Her concern is for lower-income boaters on the canal network. Many opt for a moving lifestyle to maintain financial harmony or because private marinas reject them for being full-time liveaboards, for having children, or other biased reasons. There’s a collective anxiety that future generations of itinerant boaters may never come to be, while those already here are wheedled out.

Custodians of the community

Jack Saville works for the NBTA and lives on his narrowboat in London, where CaRT claims overcrowding. He often moors in areas he recalls as being derelict when he was younger. For Saville, to lose nomadic boaters would be to lose the safety they bring to our public towpaths. Jack believes CCers are “custodians of the canals”.

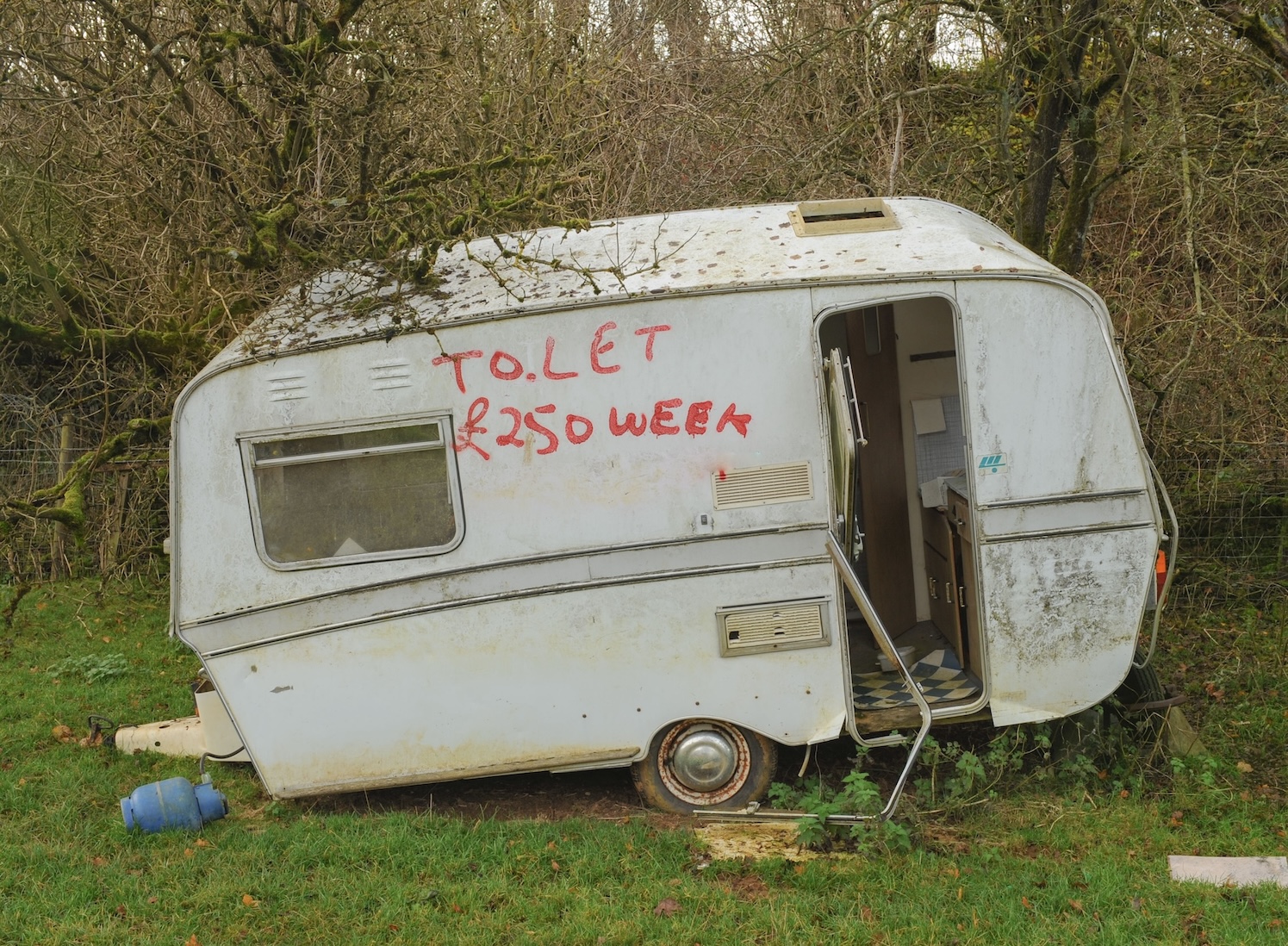

“I value people having a sense of ownership of something that feels theirs, secure and safe, but it doesn't have to be to the exclusion of someone else,” he says. “Canal boats manage both. With the housing crisis, there’s a lot of anxiety about where home is and what home can be. Boating offers an alternative way of thinking about that.”

“We can access just 11% of our green and blue spaces, and over-commercialising canal land may reduce that.”

There’s an invisible line between those who use the canals for leisure and those for whom it is home. CaRT has exacerbated that divide, proclaiming that nomadic boaters cause more erosion and use services more - without quantifiable proof.

Jack and Lisa are disappointed that CaRT doesn’t appreciate the community’s positive impact. At the protest in Birmingham, boaters from across the country shared accounts of CaRT selling culturally significant buildings, the atmosphere was one of distrust.

Jack adds: “We don't possess the canal; we have no ability or desire to exclude other people from it, but we would like to preserve it.”

The importance of boating heritage

Ancient remnants of water systems have been found at Stonehenge, a meeting place for a culture that used water as a thoroughfare, dug to carry materials from one place to another. Britain’s canals were dug for trade and industry, from pottery to coal. Products for the home ferried by those whose homes became the boats that ferried them.

I think of this history as I swing ropes and move my houseboat along the water, in line with the seasons. Itinerant boaters like me live aboard permanently, they have no land address and they move along the canal every two weeks. For me, the freedom this lifestyle once offered is fading. Others agree with me.

“We've been using these rivers to move around and remain mobile in the landscape since the Bronze Age,” Ben Bowles, a leading canal anthropologist, tells The Lead. He, too, was once an itinerant boater and recalled the optimism when CaRT took over from British Waterways to CaRT in 2012. He’s concerned about CaRT’s action against the community, believing it part of a broader problem targeting the governance of nomadic people in the UK.

In 2023, Suella Braverman called homelessness a “lifestyle choice” and pledged to rid urban areas of tents. This statement soon backfired, with Braverman’s lack of concern for hardship too harsh for the general public. The housing and economic crisis in the UK has seen homelessness increase, as well as nomadic living. What was striking about Braverman’s statement was the secondary bias contained within it. It suggests the idea of not having a fixed address holds deep prejudice in the UK.

For centuries, those who live nomadically, whether on land or water, have been depicted as anti-social. This was evident in the 2022 Police, Crime, Sentencing & Courts Bill, which enables authorities to confiscate boaters' homes as well as the homes of Gypsy, Roma & Travellers. CaRT already repossess boats they deem “unruly”. Simultaneously, #TinyHome #Offgrid commercialised versions of these lifestyles have become popular in pricey, pristine VWs and for-hire boats. The surcharges proposed won’t be applied to hire boat companies, some of the system's highest users.

“We have this kind of politics and landscape because of enclosures, the parcelling out of land, and the restriction of people's movements. So, capital becomes more liquid and mobile as people's mobility decreases,” Bowles explains.

Last year, the cost of living grant was not awarded to nomadic boaters, despite advertising promising it was for “everyone”. This was eventually rectified after a year of campaigning by boaters. The government then proceeded to axe canal funding, a plan outlined in CaRTs formation in 2012. CaRT has claimed this is one of the main reasons for sudden changes despite it being a long-term plan.

Where will CaRT get money from if boaters are chivvied out of the way? The answer is real estate – selling historical, environmental and cultural lands for short-term gain. The Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs has given the green light for CaRT to sell off these commodities without the need of government consultation. The aim: make CaRT profitable by removing all public funding, and with it public ownership. These decisions were made in their 2023 review.

“Canals are mainly profitable if you see them as a water resource, and so if the water companies end up owning the canals, everybody would be screwed because we know how water companies deal with their privatisation,” Bowles foreshadows.

CaRT stated: “The Trust is also working to generate more income from its property and non-property endowment, and other commercial sources such as hosting utilities and water transfer.”

Fighting for rights

CaRT defended the surcharge based on their self-authored survey given to boaters in 2023. They refute criticisms from boaters and the NBTA that the survey, which asked a majority if they should surcharge a minority, was biassed. They justify CCers move more than other boaters based on the fact that they monitor their movement more (a requirement set by CaRT). They claim: “While just one fifth of the 35,000+ boats on our waterways don’t have a home mooring, they accounted for three-quarters of the boats sighted using our waterways and moored on our towpaths. These boats are also more reliant on facilities provided by the Trust, leading to increased costs to meet their needs.”

They also state as being “committed to providing essential waste, sewage, and water services to boaters” despite an announcement to close numerous facilities across the country, taking away emergency-use toilets and showers completely. Whilst removal of general bins in places like Lancaster, Kennet & Avon and Craven in 2023 have now begun to effect all public users negatively.

At the end of the Birmingham rally, boaters gathered to share food, thoughts and experiences. Pamela Smith, NBTA chair, climbed the old lock gate to give an address. She proclaimed CaRT’s actions were “draconian and punitive”.

“In 2014, the NBTA started a campaign to get CaRT to abide by the Equality Act. Now, hundreds of disabled boaters no longer face losing their home if they're unable to cruise due to their disability.” She went on: “CaRT has written numerous policy papers about so-called non-compliant continuous cruisers, labelling us ‘continuous moorers’ and accusing us of being anarchists!”

This is not the first battle boaters have had to wage to ensure their rights. The River Lea campaign saw boaters fighting for moorings deemed ‘unsafe’ despite CaRT's intention to continue using the area. The NBTA took out an independent inspection, concluding the safety concerns were unbacked. This was another example of a self-conducted CaRT survey being used for significant communal change and causing residents to form defensive demonstrations, like the one in Birmingham.

“The survey was terrible,” says Bowles. “The way that CaRT framed the question problematised the idea of a continuous cruiser. In doing this, they assume that continuous cruising is a problem.” The NBTA agrees, claiming CaRT is failing to meet its duty of care, and these new charges go directly against the Waterways Act 1995.

“As long as boaters can move freely on the canal, everybody else can too; as long as nomadic boaters remain here, the canals remain here, for the public.”

“The Canal and River Trust is an underfunded, complex organisation with an almost impossible job, but many of their processes have been and are violent,” Bowles reflects.

The violence referred to is the repossessing of boats. CaRT defends its methods of eviction based on the actions of CCers and the pains of court costs. The frame evictees as ‘persistent non-compliers’, as noted during two boater evictions made by CaRT on the Kennet & Avon Canal in 2023. One of the evicted boaters, Mr Selassie, insisted he had offered to pay for a licence ‘more than once’.

Flowing forward

Gangly grey legs wade through the water, hunched in the shade where dinner hides. It’s my neighbour, a grey heron. Migration is a term we use for winter, but it strikes me that these birds do mini-migrations regularly. They meander down the canal, just like me. The inclination of movement is innate. Humans, by nature, are nomadic; it’s how we spread across the world.

As long as boaters can move freely on the canal, everybody else can too; as long as nomadic boaters remain here, the canals remain here, for the public.

The NBTA believes with the public's help, we can change CaRT’s mind. Yet, without acknowledging the community's grievance, I wonder whether Canal & River Trust is taking these concerns seriously. In 1995, the courts deemed there should be just one licence fee for all, as it would be discrimination to do otherwise. CaRT has not commented on the legality of these surcharges. CaRT continues to state the charges are to ‘keep canals alive’, but many boaters are worried CaRT’s actions may cause irreversible damage to the national heritage of boating or even dismantle Britain’s publicly accessible canals altogether.

At a time when flooding and climate change is affecting our national water systems increasingly, possible privatisation could cause more issues to all. The NBTA held a follow-up demonstration in the form of a community regatta in Paddington, London this Easter weekend with great success. CaRT again didn’t respond or show up. CaRT’s new surcharge - seen by many as penalisation of nomadic boaters - is now in effect, and a charge will be applied in addition to inflation every year for five years, unless another agreement can be met.

From a broader UK perspective, we should be concerned about our ever-shrinking access to leisure and nature. We can access just 11% of our green and blue spaces, and over-commercialising canal land may reduce that. As boaters, we are concerned about keeping our homes and community alive.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.