The Balinese spiritual-industrial complex

Bali, a longtime centre of Hinduism in Indonesia, has been transformed by Westerners seeking Instagrammable enlightenment. We take a look at the gurus and ley lines, crypto-bros and digital nomads - and speak to the indigenous healers still serving communities beyond the social media haze.

INDONESIA — At an “ancient” and “authentic” cacao ceremony in Ubud last spring, the crowd swayed as one to facilitators chanting in Sanskrit; nobody bothered to explain why these ancient Indian mantras had been repackaged into an ostensibly Native Mesoamerican ceremony on an Indonesian island. It wasn’t clear why the mostly Western, mostly female participants were earnestly praising Hindu elephant god Ganesha. After the sipping of “heart-opening” cacao, accompanied by the kind of enthusiastic acoustic guitar you might find at a church youth group, the event became an “ecstatic dance”. Participants moved and grinded unabashedly to a low-budget day rave, while a cacao-facilitator-cum-DJ overlayed Kirtan — more chanted Sanskrit mantras — onto sitar music and generic techno. The participants, young and old, were sweaty and mostly sober, dancing like nobody’s watching. There was little pretence anymore that this was an ancient, transcendent experience, but nobody seemed to mind.

Scenes like this are a far cry from those that have played out in Balinese villages for many generations. In the early 1980s, as the Western fascination with New Age spirituality waned in favour of capitalism and computers, anthropologist Linda Connor and filmmaker Timothy Asch were chronicling the work of Balinese healers a world away. Their films — legendary in ethnographic circles — document the life and work of Jero Tapakan, a balian (healer) based near the island’s centre.

We see Jero, a spirit medium and masseuse, guiding her visitors with trance as well as touch. She massages the aching belly of a man stricken by sorcery and voices the complaints of a family’s long-dead relatives. Her work, like that of other balian, is steeped in hundreds of years of spiritual tradition unique to the island.

In the decades since the films, Bali’s popularity as a tourist destination has exploded — at least in part because of its spiritual heritage. Sold as a place to “find yourself” by Julia Roberts in 2010’s Eat, Pray Love, it’s now home to a spiritual industrial complex to rival Tulum in Mexico or Machu Picchu in Peru. In the movie, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s book before it, Roberts’ character receives guidance from a real-life balian at his home in the central town of Ubud: a Balinese experience packaged relatively faithfully for Hollywood. According to some estimates, tourism increased by 400% in Ubud in the years following the movie; its local stars became minor celebrities. And it’s here that many Westerners have chosen to set up New Age spiritual businesses.

Ubud is the historic spiritual and cultural centre of the island. It is lush, green and rainy, and home to some of Bali’s most important temples, ceremonies and dances. It’s also where some New Age believers claim two prominent “ley lines” (strips of sacred power that circle the planet, popularised by the British hippy movement of the 1960s) intersect, creating an energy centre — if you’re into that sort of thing.

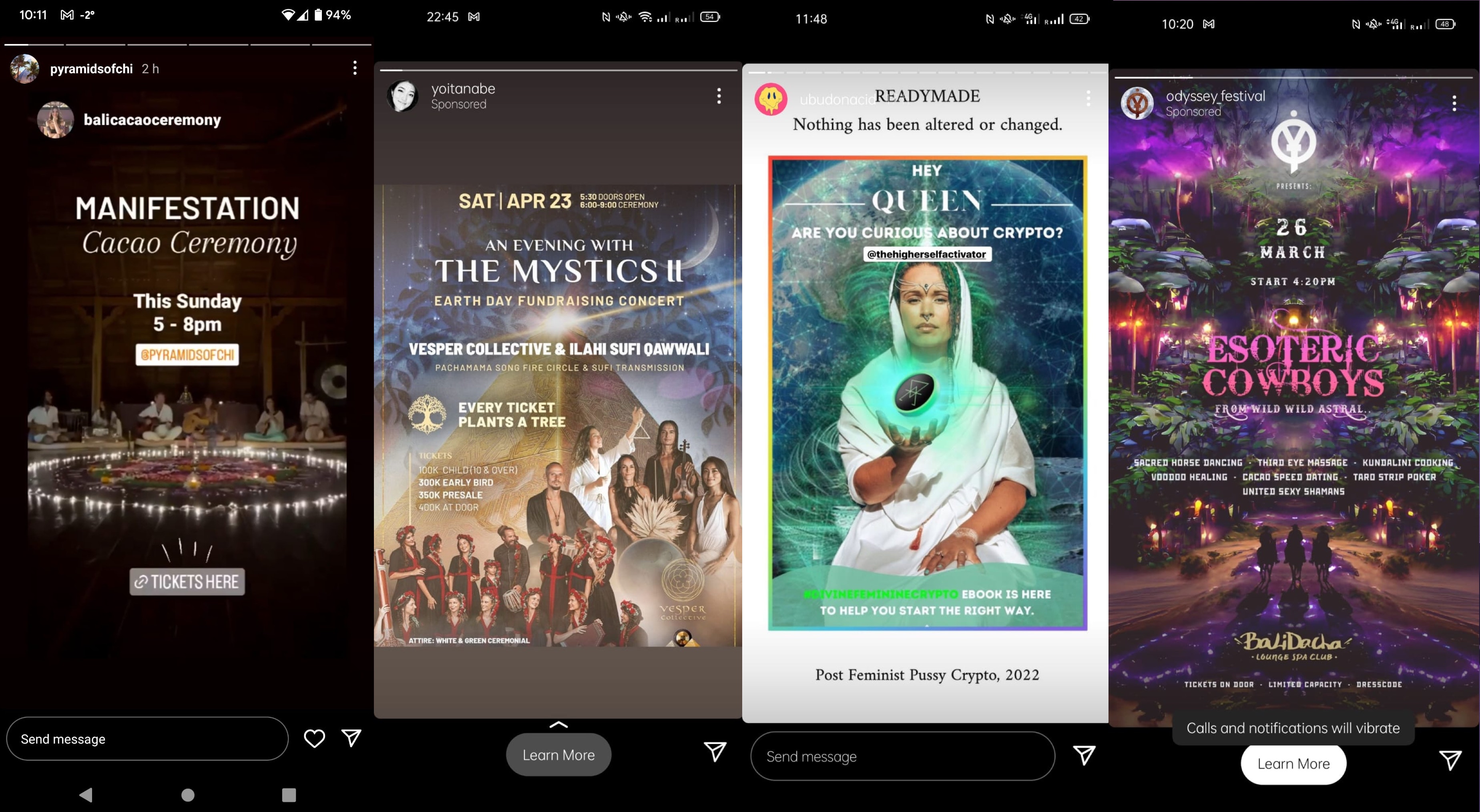

As tourist traffic has expanded from Eat Pray Love fans to crypto traders, bio hackers and digital nomads, Western-owned business have steadily adapted their offerings, selling a range of imported traditions — reiki, yoga, ecstatic dance and sound healing — through a mish-mash aesthetic of dated posters that look straight out of a Glastonbury head shop and Instagram-centric vaporwave ads.

While the digital marketplace is rife with ads for New Age healers, advertising is considered taboo by many balian, who typically gain clients by word of mouth alone. Although some traditional practitioners, including a well-known local priestess, have begun using social media to connect with clients, this is still a highly unusual practice.

Ubud-based Balinese healer Komang Darsita, who practises a traditional form of energy healing, says advertising would be at odds with his role in service to others.

“I don't need it. I never, ever use promotion. The energy is not good,” he says. “Just let people know from mouth to mouth, not by promotion on social media or whatever… for me this is egoistic. I don't want to be like this. It’s okay [if I have clients], but if not, this also doesn't matter.”

Those who’ve chosen to make the island their home for reasons other than spirituality often poke fun at the New Age “Ubud stuff.” Its reputation is regularly parodied online, whether it’s in posts on the “Ubud on Acid” Instagram account or in the satirical Bali Metaverse Quest game, where Fake Shamans and Divine Feminines battle Crypto Bros and Shitfluencers. Ironically — or perhaps grimly — this parody of monetization has itself been monetized: all of the characters can be purchased as NFTs, with listed prices reaching as high as £2,000 before the market collapsed. One of these — a trading card for a since-deported Christian influencer who performed a pseudo-Maori haka naked on the sacred Mount Batur — is rumoured to have been bought by the man it parodied.

Continued devotion

Many locals, meanwhile, are bemused by the New Age Ubud scene. “I don’t get it,” says Jim, a scuba instructor from the seaside village of Amed. “Us Balinese, we don't believe in that.”

Jim is translating at the home of local balian Wayan Kasih, who has been working as a healer for 30 years. Wayan says he spent 15 of those learning his craft in Bali and neighbouring Lombok as he proudly shows off a government-issued traditional healer’s permit. The document says he can perform services like massage, and make and administer herbal remedies. Locally, he is known as a powerful rain-stopper: a prized skill during Bali’s often thunderous six-month wet season. And, if he performs the right prayers, he says he can withstand fire.

Wayan serves other villagers and visitors from further afield, including an impressive list of politicians, and the occasional foreign tourist.

Over the course of four hours on a rainy Friday in April, three guests arrive for treatment and prayers at his home. They sit on a raised platform in the yard as they converse with the healer, chickens racing all-the-while around the garden. Conversations are interrupted by the oinking of pigs reared for ceremonial use and the heavy splattering of rain on the tiled platform roof. Wayan’s wife, whose hair — uncut for years — hangs long and heavy down her back, greets guests with cheer and sweet, unfiltered coffee. Complete with homemade arak (a local spirit) and customary sarongs and selendangs (sashes), the picture couldn’t be further from those of the tourist centre in Ubud. As Jim explains, this kind of healing has barely changed for generations.

Rice terraces near Amed, Bali. Photo: Katie Hignett

While Bali’s medical infrastructure has advanced significantly in recent decades, visits to balian remain an important part of many residents’ lives. Jim says that locals typically visit healers when Western medicine fails to explain or cure an ailment. Doctors and hospitals are usually the first port of call, but if symptoms persist, spiritual forces may be blamed.

A woman who visit’s Wayan’s house complains of a leg pain that seems always to appear ahead of religious ceremonies, making it hard for her to attend. Dark magic is considered likely, given this timing, Jim says. He explains that there are two types of spiritual healers here: ones that cure like Wayan — and ones that curse.

To diagnose the woman’s ailment, Wayan uses an old plastic pen imbued with holy energy from a silent prayer. He presses the space between her toes with the pen and, at other points, uses a small piece of wood bequeathed by his former teacher. The physical nature of these everyday objects isn’t important. Like Catholic holy water, they become special when they are blessed. The woman’s response to Wayan’s pen determines how and where he will massage. As the problem is in her leg, he sticks to the feet and ankles, occasionally applying homemade ointment from a dusty glass bottle.

Guests usually bring offerings to a healing that can include cash alongside rice and other staples. The more serious the ailment, the more a patient is likely to donate. But there’s no fixed price for cures, and no obligation to pay. Because of this, a healer’s income is usually unpredictable. Balian, who are often descended from a line of healers, don’t usually seek out their profession, but are “called” to help others, Jim explains.

Although he mostly serves Balinese people — especially during the pandemic, when few international visas were available — Wayan is not isolated from the island’s tourist bubble. Home to pristine ocean waters and vibrant coral reefs, Amed is normally a thriving destination for snorkelers and divers. Before the pandemic, Wayan had agreed to teach a small number of foreigners some of his healing practices. Indeed, many bule (foreigners) engage with local traditions, sometimes alongside New Age practices.

Wayan says he isn’t against foreigners importing other healing practices to Bali. He’s “open” to the notion they might work if people believe in them. “Everyone can bring these from [other countries] to Bali. It’s fine.”

But he and other Balinese will stick to their own beliefs. “If people believe in me, I can help them in my way. We pray in the temple and to the God that we believe [in].”

Wayan kasih, a balian (healer) in Bali, April 2022. Photo: Katie Hignett

Jim says Bali’s religious heritage isn’t at risk of dilution by tourists. He explains the island owes its spiritual status not to “ley lines” and “energy vortexes”, but to the continued devotion of its inhabitants to traditional rituals that honour spirits and ancestors. Like generations before them, young Balinese still pray daily and visit their mother temple, he says. “We still keep the annual silent day (Nyepi) from hundreds of years ago,” he says. “We close the airport every year. It’s 2022 and we still do it. It’s not going to change.”

This rich cultural heritage is plainly visible to visitors. Whether there are tourists or not, Balinese people place offerings of flowers, incense, fruit, cigarettes and plastic-wrapped sweets outside homes and businesses every morning. Traffic is routinely halted for ceremonies and traditional dances that often spill out onto the street.

The darker side

Filmmaker Govida Wayan (not his real name) wants to refocus the Western gaze from the New Age services foreigners travel for, back onto the island’s own rich spiritual history. “It’s a little bit ironic,” he says. “Tourists come to Bali. Okay, like you can enjoy life here, you can get fucked up. You can maybe make a business here. But is that the real attraction? I mean, you can do that everywhere…I'm not judging you, but this is what I see.”

He set up an anonymous Instagram account — Ubudcult — to try and bring accessible, educational content about the island to its internet-addicted visitors. An Indonesian from Java, he is enamoured with the unique mysticism of Balinese Hinduism, and he uses the account in part to showcase hyperlocal ceremonies he fears might one day be lost. With different traditions found from village to village, the events are diverse and incredibly difficult to track down if you’re not a local. Advertised in Balinese, if at all, and featuring elaborate costumes, dances and props, as well as hard-to-interpret activities like trance, they can be highly inaccessible for an outsider. Govida posts videos of these events online with English-language descriptions.

He and other contributors want the account to function as an antidote to a wealth of uncritical content promoting Bali’s New Age industry. Bitesize explainers provide tongue-in-cheek critiques of the egocentrism of astrology and serious takedowns of the capitalistic and arguably predatory elements of the spiritual industry. At the end of each read the words: “Trust no-one but yourself. Remain sceptical.”

While Govida says he “doesn’t judge” people who come to Bali and engage with New Age practices, he has serious concerns that vulnerable visitors may be drawn in by practitioners that aren’t equipped to deal with their problems.

This is a common criticism of the wellness industry, with life coaching in particular often criticised for a lack of regulation that enables individuals to market themselves as consummate professionals on the basis of flimsy accreditation. In Bali, “coaching” techniques often overlap heavily with the New Age, where magic is packaged alongside meditation as a means to achieving personal growth.

With so many foreigners seeking spiritual solace on the island, Govida is concerned that unscrupulous — or even just naive — practitioners may end up doing more harm than good. “If you offer sessions like trauma healing, it's a really tricky topic. You can either really help, or you make it worse,” he says. “Some people just don't care. [They think] I want to live in Bali, I don't want to be in my country. So [they do their] best, but some people really get a bad experience.”

This kind of attitude is “completely dangerous,” he says. “I see so much dangerous stuff in this Western spirituality and I feel that these kinds of things need to be pointed out.”

Govida isn’t alone in his concern. Bloggers claim near-fatal accidents have occurred at ill-prepared retreats and that allegedly predatory yogis have been hosted in Ubud. While The Lead has been unable to verify these specific claims, harmful attitudes are openly promoted by some wellness businesses in Bali. Just this week, prominent Canggu yoga centre “The Practice” uploaded an arguably transphobic post to its Instagram page in the form of an imagined dialogue on pronouns between two Hindu gods.

Govida says people travel to the island without a good understanding of either Balinese healing or the New Age industry that’s become so prominent, leaving them vulnerable to bad actors. Doing this kind of stuff “under the name of spirituality… I feel so disrespected by that.”

Western spiritual entrepreneurs like Peter McIntosh don’t necessarily disagree. McIntosh, who has a corporate background, co-founded the Ubud juggernaut Pyramids of Chi: a sound-healing centre he was inspired to open after experiencing a “vision” of two pyramids during his third attempt at retirement.

He says there “an element of lack of authenticity from certain people that does show up here,” with some businesses “more driven by commerce” than client wellbeing. He is adamant his own company — which has seen more than 225,000 attendees pass through its doors — is driven not by commercial success but by a real desire to heal.

A selection of Instagram ads for "spiritual" events on Bali, 2022.

Set up by Peter and his wife Lynn in 2013 with the aid of a Craiglist fundraiser, the business’s literal pyramids (one dedicated to the Earth, one to the Sun) have come to dominate the New Age landscape in Ubud. Inside, visitors are bathed in vibrations from gongs, sound bowls and other percussive instruments over a ninety-minute session. Depending on whether you go for sound healing only or a light-and-sound waterbed experience, a session costs between £15 to £40. Minimum wage in Bali is £142 a month.

Whether you believe the gongs will align your chakras or not, the sessions are nonetheless immersive and relaxing. The musical skill of their facilitators is evident in the rich soundscapes created: sweet bird song, leaves rustling in the breeze, water flowing through a stream and sometimes, great, tumultuous storms.

After a Saturday morning session in early April, at least three of the eight attendees appear to need some level of consolement. MckIntosh says he must be “satisfied” that anyone who runs a session can deal with these sometimes highly emotional responses, but doesn’t elaborate what official certification of this ability is required.

“I've seen just about every kind of healing you could possibly imagine happening inside,” he says. “Most of us are under stress. Most of us are carrying around a weight of worry on our shoulders. Concerns could be financial, they could be relationships, they could be health. It can be a multitude of things occurring.”

In spite of his professed concern that vulnerable visitors to Bali might be taken in by inexperienced or naive practitioners, as recently as this summer marketing materials for a breathwork event hosted by the Pyramids suggested it could help those who’ve experienced serious childhood trauma. “Soulify” sessions promised to help “safely” heal the damaged “inner child” within, listing possible causes like sexual assault or growing up in a cult.

Load that same page today, and references to the roots of childhood trauma are gone, replaced with a disclaimer that all participants attend at their own risk. The Lead has asked both Reid and McIntosh what prompted this change, but received no specific answer by the time of publication.

Information is still scant as to what qualified its facilitator, Scottish spiritual coach Mark Reid, to deal with this kind of trauma. Claims he cured his own cancer through spiritual healing, however, remain live. The Lead has asked Reid for more information about these claims, and also received no answer.

McIntosh says his company takes client safety “seriously”, only allowing new facilitators to operate at the centre after the management team have reviewed client testimonials and tried out a session for themselves. “To date we have had excellent feedback from Mark's guests, and some of those [are] very profound, so we are comfortable he knows what he is doing,” he said.

*

Although Wayan Kasih isn’t particularly worried about the impact of New Age businesses on Balinese culture, he is also concerned that people come to the island and market themselves as healers without appropriate experience.

“I tell the truth,” he says through translator Jim. “The bules that do healing; they could be lying. They could be learning from articles and things, and now they’re in Bali they could be telling lies. I’ve been learning this for almost 15 years and I am connected with God. These Westerners, I’m not sure about them.”

He says he’s 50/50 on whether such practices can work or whether they’re just made up. “If you want to see a healer in Bali, go to a Hindu healer,” he says. “Don’t go to someone in Ubud because they have a five-star review or something like that.”

Even among balian, suspicion that power and influence are being misused is common. Komang Darsita is sceptical not just of imported practices but of some Balinese healers he says rely on “negative” energy. He spent years as a young man searching for a teacher he trusted to employ only “positive” techniques. Eventually he found a “humble” healer who, much like Jero Tapakan, laughed and joked with clients as he treated their ailments.

Unusually, Komang travelled with this teacher not just around Bali but internationally, flying to the Czech Republic as a pupil. When there, he says he was surprised to find the same spiritual ailments he sees among his Balinese clients. Alongside the mental and physical illnesses that might require a medical doctor, he believes some of his Czech customers were stricken by dark magic or negative energy. Describing an encounter with a melancholic spirit he says took the form of a woman hiding in a forest, he says: “There are many, many sadness spirits there.”

Balinese or bule, visitor or local, Komang says, “the same spirits” haunt us all.

The Lead is now on Substack.

Become a Member, and get our most groundbreaking content first. Become a Founder, and join the newsroom’s internal conversation - meet the writers, the editors and more.